#NephJC Chat

Tuesday Sept 22 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday Sept 23 9 pm BST and IST

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, dgaa619, https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa619

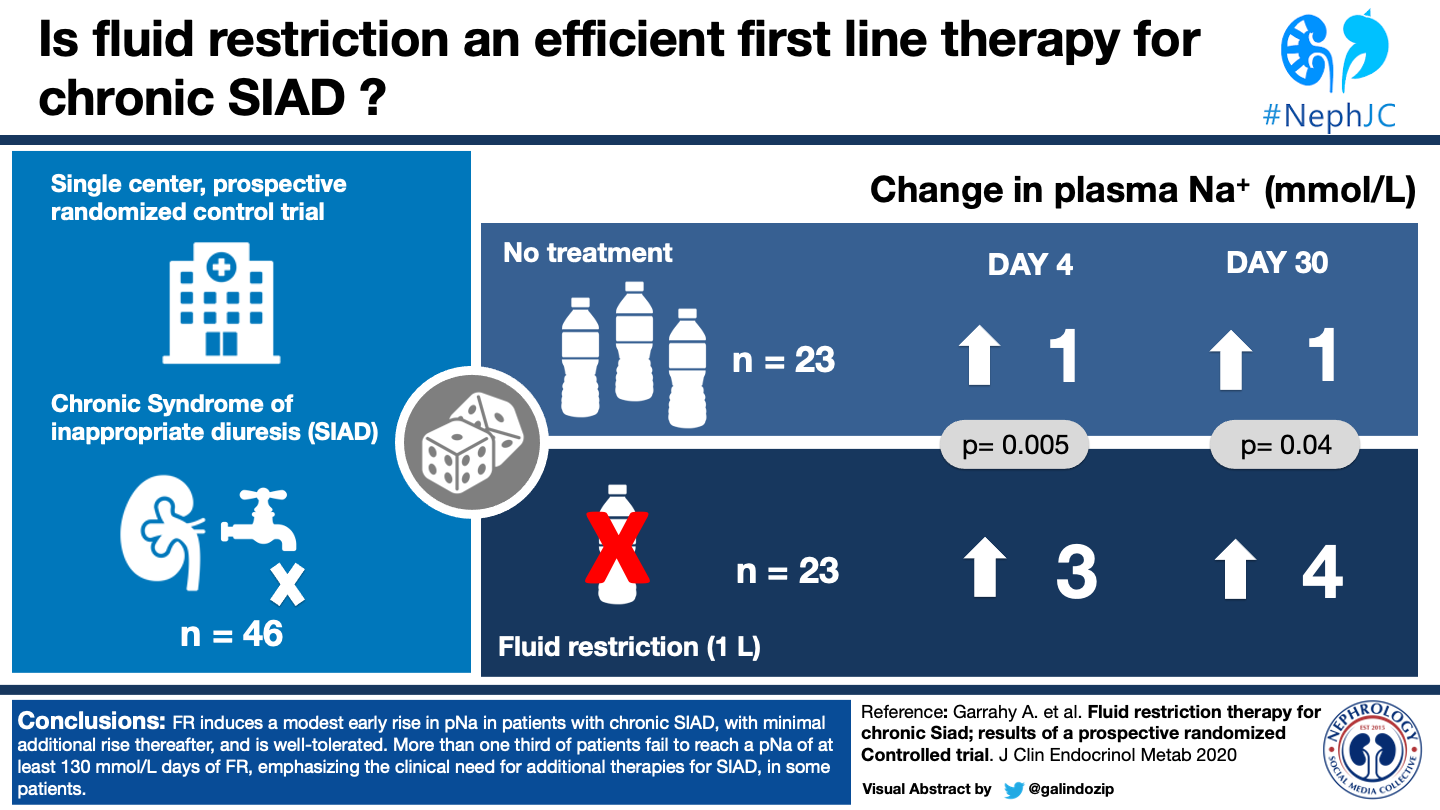

Fluid Restriction Therapy for Chronic Siad; Results of a Prospective Randomised Controlled Trial

Aoife Garrahy, Iona Galloway, Anne Marie Hannon, Rosemary Dineen, Patrick O’Kelly, William P Tormey, Michael W O’Reilly, David J Williams, Mark Sherlock, Chris J Thompson.

PMID: 32879954 Full Text at Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism or Sci-Hub

INTRODUCTION

For a speciality that prides itself on intimate knowledge of dysnatremia, nephrologists have been working with precious little information the last few decades. We have rounded for years armed with nothing but theory and only recently (with, and perhaps because of, the advent of expensive drugs to be justified) have those theories been tested. As detailed in Joel Topf’s recent blog post on the topic, the list of what we don’t know is pretty staggering and only recently has some headway been made:

Is mild hyponatremia actually bad? Maybe, probably. Falls, and some daily living impairment in elderly patients.

Ok, but does fixing the hyponatremia fix the problem? Yes, finally a meta-analysis in 2015 concluded reduced mortality. No new guidelines have been published since then, though, and the European Renal Best Practice group’s published guidelines in 2014 recommend against treating mild hyponatremia.

Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 29, Issue suppl_2, 1 April 2014, Pages i1–i39, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfu040

So what’s a safe sodium? We don’t know. Most people use 130 mmol/L as a cutoff but again, not tested. An observational study in 2019 found improvements in functional scores in the elderly only when plasma sodium increased by more than 5mmol/L over baseline. Today’s study includes both.

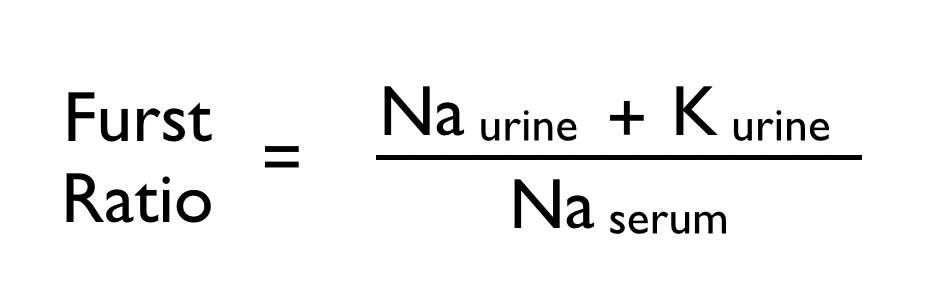

How do we fix hyponatremia? Fluid Restriction! That works, right? Maybe. Though it is the first line therapy recommended, this is not based on….any trials! What we do have is the Furst equation, which is useful to predict whether or not our patient will respond to fluid restriction. (But don’t get too comfortable with that ‘til you’ve read today’s study)

A first ratio over 1 indicates that fluid restriction alone will not be effective at correcting the serum sodium. Furst H, Hallows KR, Post J, et al. The urine/plasma electrolyte ratio: a predictive guide to water restriction. Am J Med Sci. 2000;319(4):240-4.

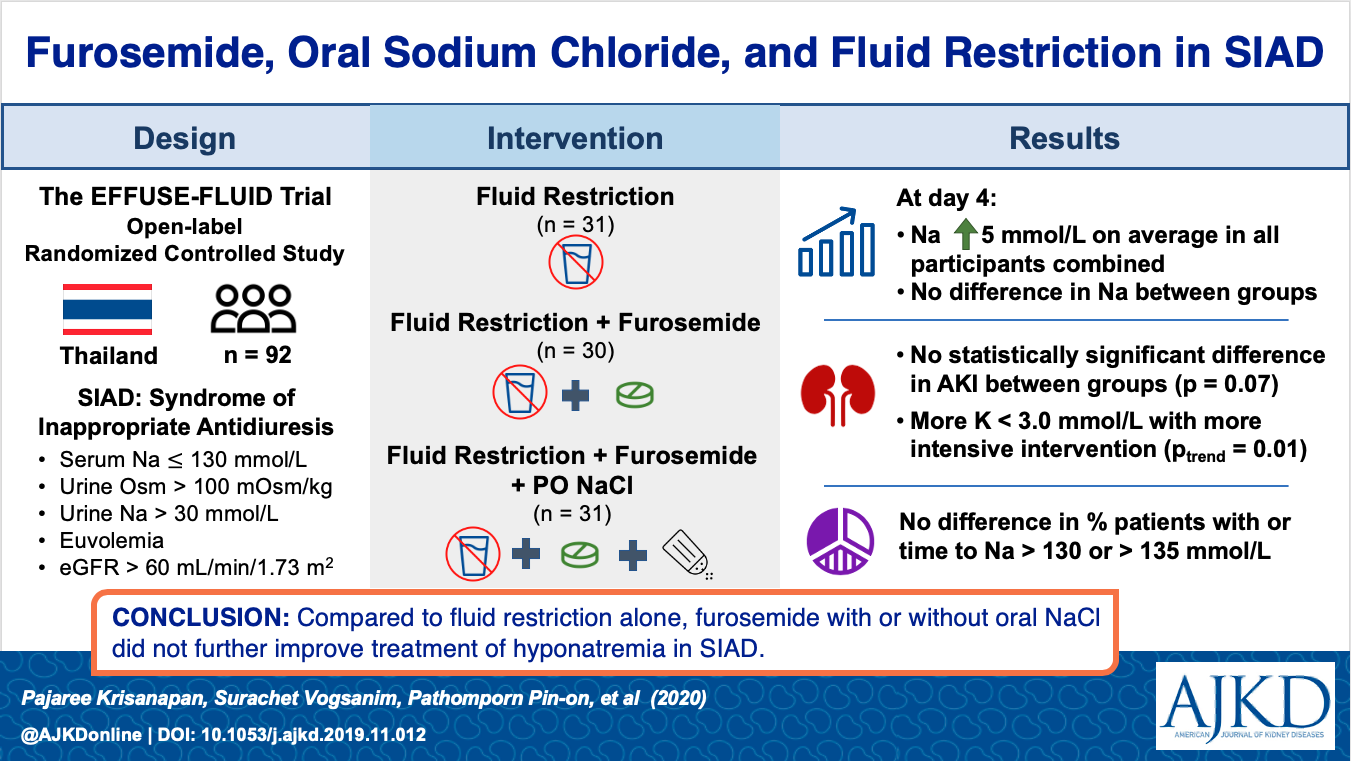

Well, but what if we add Lasix? Or salt tabs? Nope. Doesn’t work any better than fluid restriction alone, at least not in 2020 randomized controlled trial EFFUSE-FLUID (Krisanapan 2020).

Of course, none of this is to say that fluid restriction, or loop diuretics, or salt tabs don’t work. There’s just not great evidence for any of it.

So we are left with:

Don’t treat hyponatremia just for the sake of treating hyponatremia. Or do. And if you do, just fluid restrict. Or add adjunct therapies.

Pretty maddening in a world of evidence-based medicine, but things are looking up. So far, 2020 has brought us a randomized controlled trial of adjunct therapies (Krisanapan) and Refardt et al’s RCT of empagliflozen for SIADH and now, we have the first randomized controlled trial of fluid restriction itself (there was no placebo group in the EFFUSE-FLUID tral.)

THE STUDY

Methods

Patients with SIAD were recruited from a single teaching hospital in Dublin, Ireland from medical, surgical, and oncology wards, as well as from the endocrinology clinic.

Study Population

Inclusion Criteria:1. Euvolemia (assessed clinically)2. Plasma sodium (PNa) Na 120–130 mmol/L for 48 hours3. Urinary sodium concentration (UNa) ≥ 30 mmol/L4. Urine osmolality (UOsm) ≥100 mOsm/kg5. Normal adrenal function 6. Normal thyroid function

Exclusion Criteria:1. Hyponatremia with symptoms of cerebral irritation (headaches, confusion, seizures, drowsiness). 2. Underlying cause of SIAD recognised which was reversible with treatment of the underlying condition (e.g. post-operative SIAD, pneumonia)3. Hyponatremia-causing medications which had been discontinued. 4. Subject required intravenous fluids 5. Alcohol excess6. Diuretic therapy 7. Renal, liver or cardiac failure8. Subarachnoid haemorrhage 9. Subject already on fluid restriction

Procedure

Patients were randomised, using a computer-generated randomisation table in random permutated blocks of four, in a 1:1 ratio to either fluid restriction (FR) or to no specific hyponatremia treatment (NoTx) for one month. The study was open label. Patients in the fluid restriction group were instructed to limit fluids to 1 liter per day. Patients were evaluated at baseline, Day 4, 11, 18 and 30. Withdrawal criteria: pNa fell by 5 mmol/L from baseline, or to <120 mmol/L. Other hyponatremia treatments were not allowed during the course of the study.

Endpoints

Primary: Change in plasma sodium 9pNa) at Day 4 and Day 30 Response to FR was defined as an increase in pNa at day 4 of 3 mmol/L

Statistical Analysis

Power calculations indicated that a sample of 17 patients per treatment arm was required for a power of 80% to show non-inferiority at the 5% level of significance, and a sample of 23 patients per group for a power of 90%. Efficacy analysis was conducted following the Intention-To-Treat principle. Mann Whitney U test was used to compare continuous data and Fisher Exact test to compare categorical data across two groups. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to test the significance of changes in pNa, UNa and UOsm over study timepoints. A p-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

There were 56 participants, 46 recruited and underwent randomization. Of these, 23 received no treatment and 23 were fluid restricted. All 46 had 4-day results, but at 30 days there were only 17 in the FR group and 15 in no treatment (figure 1.)

Fig. 1 from Garrahy, et al, J Clin Endocrinol Metab

Demographics are adapted from Table 1 of the manuscript below. Median baseline pNa was similar in the two groups (127mmol/L v 128mmol/L), as was Urine Na and Urine Osm. The Fluid restriction group had a mean duration of hyponatremia of 19 months whereas the No Treatment group had 71 months mean duration. The two groups also differed in etiology of SIAD - more patients in the fluid restriction group had respiratory disease (5 vs 3) and idiopathic SIAD (9 vs 6), while fewer had CNS pathology (0 vs 3).

Fig 2, Garrahy, et al, J Clin Endocrinol Metab

As hoped, there was a statistically significant difference in fluid intake between the FR and NT groups as shown in Figure 2d, with a mean intake of 1L reported at all timepoints by the participants in the FR group. The amount of fluid intake in the NT group was near 1500mL at all timepoints. That said, the mean urine osm of the FR group decreased after day 4.

As shown in Table 2, By Days 4 and 30 after randomization, the fluid restriction group had a mean of 3 and 4 mmol/L increase in plasma Na, respectively, whereas the group randomized to receive no treatment, sodium increased by 1 mmol/L at both timepoints. It is worth noting that only 15 of the 23 patients were followed to 30 days, although this was also the case in the group which was not fluid restricted. Table 2 provides additional details about the proportion of participants who had increases of ≥3 mmol/L (56.5% in restriction group, 26% in the no treatment at 4 days) and those who achieved a serum sodium of ≥130mmol/L (61% in restriction group, 39% in the no treatment group at 4 days.).

Notably, though fluid restriction did produce a significant difference in overall plasma sodium, it produced no significant difference in the secondary endpoints of ≥3 mmol/L rise, ≥ 5mmol/L rise, or reaching 130 mmol/L level when compared to the no treatment group. Despite this failure to reach statistical significance, 71% of the fluid restriction group achieved a serum sodium of over 130 mmol/L by day 30.

Table 2, Garrahy, et al, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Change in plasma sodium concentration in patients randomised to fluid restriction and no treatment.

When considering previously reported predictors of nonresponse (UOsm >500 mOsm, Fürst equation >1), neither predicted treatment response in this study. As shown in Table 3, half the patients in the FR group who had elevated UOsm had a 3mmol/L or greater increase in pNa (compared to 60% in the group with lower UOsm), and a quarter of those with Furst equation >1 had the same increase (compared to 61% in the group with Furst <1).

In the FR cohort, there was no significant difference in median self-reported daily fluid intake in responders versus non-responders and level of supervision did not significantly affect treatment response; in fact 50% (9/18) of hospital inpatients had a rise in pNa 3 mmol/L at 4 days compared with 80% of outpatients (4/5).

Table 3, Garrahy, et al, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Change in plasma sodium concentration, and rate of correction 3 mmol/L, 5 mmol/L and to 130 mmol/L according to predictors of non-response.

DISCUSSION

There is a strong association between chronic hyponatremia and instability-related morbidity and mortality, that is, even if a patient isn’t having neurologic impairment in an office exam, mild hyponatremia is a problem. Some studies have shown improvements in activities of daily living scores and overall mortality when serum sodium is improved though this is limited to geriatric population. This is far from a settled score, however, and the European Renal Best Practice guidelines recommend against treating mild hyponatremia.

Currently fluid restriction is recommended as first line therapy for observational and intuitive reasons but has not been previously tested in a randomized, prospective trial. The cutoff which has been shown to improve outcomes is >5mmol/L increase in PNa from baseline (improved cognition and functional scores in the elderly) but this study also included pNa of 130mmol/L as it is a common anecdotal target. This study demonstrated efficacy of FR to reach an endpoint of 130mmol pNa for 71% but for most patients this did not meet the threshold of >5mmol over baseline.

When considering cost of therapy, the authors note that AKI occurred in only one patient in the FR arm and attribute this difference from other studies to their restriction of loop diuretic use and relatively liberal fluid restriction of 1L. Certainly when compared to Tolvaptan, Ure-Na, and SGLT2 inhibitor therapy, fluid restriction is the most convenient financially.

Strengths and Limitations: The main limitation of this study was modest size. Although the trend between FR and NT groups was toward a large number of patients in the FR group reaching the goal serum Na of 130 mmol/L, for example, this difference did not reach statistical significance. As nephrologists, we must also bear in mind that the two groups had average durations of hyponatremia of 19 and 71 months, which may not align well with our typical referral.

Generalizability of the reported adherence to FR therapy may be limited given the selection bias noted by authors- patients agreeable to participation in a study of fluid restriction may not reflect the population as a whole. Though the patients self-reported near perfect adherence to their one liter restriction, their average urine osmolality increased after day 4 (Figure 2.) Unfortunately, the authors did not include any parameters related to patient satisfaction, and the rate of dropout patients was similar in each group. We are then left to wonder about the only true cost of fluid restriction- patient satisfaction.

As noted by the authors, the randomized design of this study and the strictness of inclusion criteria were notable strengths. No patients with known reversible etiologies were included, however it is worth mentioning that many of the patients included in the study had idiopathic etiology and 40% of the No Treatment group achieved a serum sodium of at least 130mmol/L by day 30, highlighting the sometimes transient and nebulous nature of SIAD as a state.

Although this study was modest in size, its value as the first prospective, randomized trial of fluid restriction remains. Two predictors which had been previously validated in a larger retrospective analysis - urine osmolality over 500mOsm/kg and Furst equation >1- were not predictive of fluid restriction response in this trial.

CONCLUSION

Can patients with SIAD be fluid-restricted back to health? Not based on these results. While this study showed a significant difference in serum sodium was achieved with fluid restriction, the degree to which sodium was increased was an equally important finding. If fluid is effective but insufficient to restore serum sodium to proven parameters, as this study showed, we are left with the challenge of identifying adjunct therapies which are safe and cost-effective. But if your goal is to achieve a serum sodium of 130 mmol/L for your patient, fluid restriction may be more effective than you may have thought- if you can get them to do it. It’s certainly affordable.

In short, this study is valuable not for the endpoint it shows, but for the dogmas it calls into question.

Summary by Anna Gaddy

Chief Fellow Indiana University

NSMC Intern