#NephJC Chat

Tuesday Apr 6, 2021 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday Apr 7, 2021 9 pm IST

Wednesday Apr 7, 2021 9 pm BST

N Engl J Med. 2021 Mar 4;384(9):818-828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008290

Terlipressin plus Albumin for the Treatment of Type 1 Hepatorenal Syndrome

Florence Wong, S Chris Pappas, Michael P Curry, K Rajender Reddy, Raymond A Rubin, Michael K Porayko, Stevan A Gonzalez, Khalid Mumtaz, Nicholas Lim, Douglas A Simonetto, Pratima Sharma, Arun J Sanyal, Marlyn J Mayo, R Todd Frederick, Shannon Escalante, Khurram Jamil, CONFIRM Study Investigators

PMID 33657294

Introduction

As a great American philosopher William James said: “Is life worth living? It all depends on the liver.” Severe hepatic dysfunction complicated by hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) carries a poor prognosis and requires proven treatment strategies. The CONFIRM trial aims to provide us with such an option.

The term hepatorenal syndrome (together with so-called liver death) was first introduced in 1939 (Wilensky A., JAMA Surgery, 1939) to describe acute kidney injury after biliary surgery or hepatic trauma.

Traditionally, HRS has been classified into two distinct clinical types:

Type One - characterized by an abrupt decline in renal function (happening in less than 14 days), defined as doubling of baseline creatinine level to above 2.5 mg/dl or a 50% reduction in creatinine clearance to less than 20 ml/min.

Type Two - slowly progressing kidney dysfunction, clinically translating into diuretic-refractory ascites (Salerno F. et al., Gut, 2007).

Since 2015 the International Club of Ascites (ICA) classifies HRS-1 as HRS-AKI (Angeli P. et al., Gut, 2015), and the new definition is based on:

Diagnosis of acute kidney injury (AKI) according to ICA-AKI criteria (rise in creatinine ≥0.3 mg/dl within 48h or increase ≥50% from baseline).

No response after 2 days of diuretic withdrawal and plasma expansion with albumin.

Absence of shock and no current nephrotoxin exposure.

No signs of functional or structural kidney injury (absence of proteinuria>500 mg/day, hematuria(>50 RBCs per hpf), normal kidneys on ultrasound).

The pathophysiology of HRS informs our treatment options (Angeli P. et al., J of Hepatology, 2019). One newly discovered player is systemic inflammation, frequently due to bacterial translocation or systemic infection. That leads to innate host immunity activation, release of reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Together with portal hypertension, this causes splanchnic vasodilation and a reduction in systemic vascular resistance. Combined with inadequate cardiac output, the outcome is decreased kidney perfusion and falling GFR. Proof of this concept is shown as the vasoconstrictor-induced increase in mean arterial pressure in HRS-1 correlates inversely with changes in the serum creatinine level (Velez J. C. et al., Nephron, 2015).

Enter terlipressin - a prohormone of lysine-vasopressin and a strong contender in the hepatorenal region of NephMadness 2019 (though the blue ribbon panel failed to allow it to progress). Terlipressin has vasoconstrictor activity in the splanchnic and systemic vasculature. Within 30 minutes of administration it decreases hepatic and renal arterial resistive index, increasing systemic vascular resistance and mean arterial pressure (Narahara Y et al., J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2009). It has been evaluated in previous randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled trials (remember this NephJC summary from 2015?), reversed HRS in 42% of the patients versus 26% of controls in this 2018 meta-analysis of available data (although it was not superior to noradrenaline) (Wang H. et al., Medicine, 2018). However, a big advantage of terlipressin over noradrenaline is that it can be given on normal medical wards, whereas noradrenaline requires a central line and ICU admission for administration.

Terlipressin data from smaller studies has already led to its inclusion in the Clinical Practice Guidelines in Europe. The story of trying to gain terlipressin approval in the USA and Canada has been fascinating (and see the discussion below for more intrigue). Prior to this trial the smaller industry-funded trials of OT-0401 (Sanyal A. et al., Gastroenterology, 2008), and REVERSE (Boyer T. D. et al., Gastroenterology, 2016) had failed to win Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, and more data had been requested due to safety concerns. It is no secret that Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals hoped this trial would be the final chapter in convincing the FDA to approve terlipressin for HRS-1 in the US.

Methods

Funding

The trial was funded by Mallinckrodt - the company that bought the licensing rights from Ikaria in 2015 (who bought it from Orphan therapeutics before that). The trial was designed by the sponsor, together with the second author (from Orphan therapeutics). The analysis was done by a statistician employed by Mallinckrodt (S.E. one of the authors). So the academic authors did not design the trial, nor perform the analysis. They did write the manuscript however. .

Objective

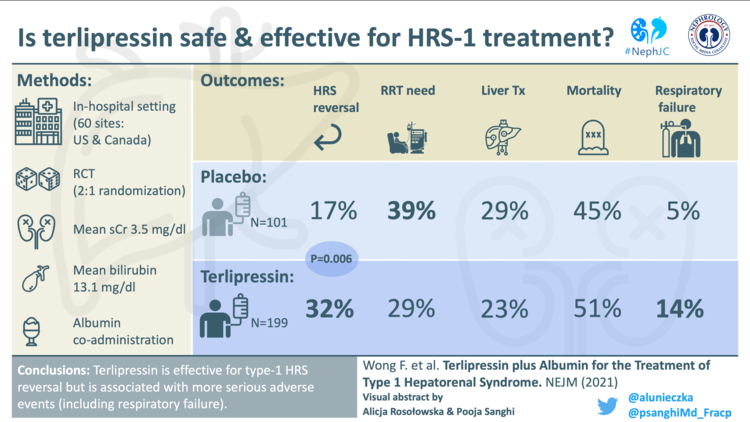

The main objective, as stated by the authors, was to confirm (CONFIRM Study) the efficacy and safety of terlipressin plus albumin, as compared with placebo plus albumin, in adults with cirrhosis and HRS-1.

Design

The study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, and developed under a special protocol assessment agreement with the FDA as a phase 3 registration trial.

Setting

It was conducted between July 13, 2016, and July 24, 2019, at 60 sites in the United States and Canada.

Patients

Inclusion criteria:

18 years of age or older,

Cirrhosis and ascites,

Increased creatinine (SCr) of at least 2.25 mg/dL (199 μmol/L), and predicted doubling of creatinine within 2 weeks (note: higher values than in the new HRS-AKI definition),

No sustained improvement in kidney function at least 48 hours after both diuretic withdrawal and plasma volume expansion with albumin

Exclusion criteria:

Creatinine greater than 7.0 mg/dl,

Large volume paracentesis within 2 days of randomization,

Sepsis and/or uncontrolled bacterial infection,

Shock,

Current or recent (4 weeks) exposure to nephrotoxins,

Estimated life-expectancy of less than 3 days,

Superimposed acute liver injury due to drugs,

Proteinuria, obstructive uropathy, parenchymal kidney disease, tubular epithelial casts/hematuria,

Severe cardiovascular disease,

Renal replacement therapy within 4 weeks of randomization,

Transjugular portohepatic systemic shunt placement within 30 days of randomization,

Use of vasopressors within the prior 14-day screening period (patients receiving midodrine and octreotide could be enrolled).

Randomization

Patients were randomly assigned, in a 2:1 ratio, to receive terlipressin plus albumin or placebo plus albumin; randomization was performed with the use of independently generated codes. Stratification was based on creatinine level (>/< 3.4 mg/dL aka 301 μmol/L) and pre enrollment large-volume paracentesis.

Intervention

1 mg of terlipressin or placebo was administered intravenously over 2 minutes every 5.5 to 6.5 hours, together with albumin (which was “strongly recommended” to be 1g per kg of body weight to a maximum of 100g on day 1, and 20-40 g/day thereafter, though volume was not enforced by protocol). Treatment was continued until 24 hours after a sCr value ≤1.5 mg/dL was obtained, or up to a maximum of 14 days. If SCr decreased by <30% from the baseline value on day 4, the dose of study drug was increased to 8 mg/day.

Figure S1 from Wong et al, NEJM 2021

Primary Outcome

Verified reversal of HRS, defined as two consecutive sCr measurements ≤ 1.5 mg/dl (the “usual” definition of HRS reversal is from previous trials - sCr <1.5 mg/dl, two consecutive measurements is a more stringent definition) at least 2 hours apart up to day 14, and survival without renal replacement therapy for an additional 10 days.

Secondary and Other Efficacy Endpoints

Secondary efficacy endpoints were: incidence of subjects with HRS reversal, durability of HRS reversal, incidence of HRS reversal in the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) subgroup, HRS recurrence by day 30.

Among many other efficacy endpoints, transplant-free survival up to 90 days and overall survival at 90 days were assessed. Data on adverse events was collected for up to 7 days, serious adverse events for up to 30 days after treatment period, and mortality data for up to 90 days after the first dose of terlipressin or placebo.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 300 patients was expected to provide 90% power to detect a significant difference between the groups. Efficacy analyses were performed in the intention-to treat population. Multiple imputations were used to account for missing endpoint data. A Hochberg procedure was used to adjust for multiple testing of the four secondary endpoints. For those of us mortals who don’t understand it - it’s a popular method for controlling the False Discovery Rate and helps to get rid of type I error (bring on all the memes).

Results

2320 patients were screened, of whom 344 had HRS type 1 and cirrhosis. Of these 309 were eligible, and 300 were actually enrolled and randomised (figure 1 below, as well as figure S2 have all the details).

Figure 1 from Wong et al, NEJM 2021

A total of 199 patients were randomised to receive terlipressin and 101 to placebo. The rationale for 2:1 randomization is not explicitly stated, though the technique is sometimes used if more data is wanted about adverse events of treatment, or if recruitment is anticipated to be difficult (it can be easier to enroll patients into a trial if the patient has higher likelihood of receiving the “active treatment”).

The baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients are demonstrated in Table 1. Points to note:

The mean SCr was 3.5 mg/dL (308 μmol/L) and mean bilirubin was 13.1mg/dL (224 mmol/L) - this is a very sick group of patients,

Around 60% of participants in each arm were previously receiving midodrine and octreotide,

Albumin was received by 99% of participants in both groups prior to treatment initiation (mean 335g in terlipressin group, 371g in placebo group) which probably explains the almost normal serum albumin levels, unlike your typical HRS patient; over the treatment period concomitant albumin was given to 83% in the terlipressin group (mean total dose 199g±147g) and 91% in the placebo group (mean total dose 240g±184g),

At baseline 28% of patients in the terlipressin group were on the transplant waiting list, versus 20% in the placebo group (Supplementary appendix, table 6).

Table 1 from Wong et al, NEJM 2021: Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline. Note that the causes of cirrhosis add up to > 100%.

Outcomes

In the terlipressin group 32% of patients achieved the primary endpoint of verified reversal of HRS-1, versus 17% in the placebo group (p=0.006) (Table 2).

Table 2 from Wong et al, NEJM 2021: Primary and secondary efficacy endpoints

Granular details of when these events occurred by group is shown in figure S3a

Figure S3a from Wong et al, NEJM 2021

For HRS reversal, the subgroup analysis is shown in figure S10

Figure S10 from Wong et al, NEJM 2021

The proportion of patients requiring RRT was lower in the terlipressin group, but proportions receiving a liver transplant and mortality were no better than in the placebo group (Table 3). By day 90, death had occurred in 51% of the terlipressin group and in 45% of the placebo group.

Table 3 from Wong et al, NEJM 2021: additional secondary endpoints assessed at Days 14, 20, 60, and 90.

For the survival curves, you have read the supplement: in particular figure S6 shows the overall and transplant free survival.

Figure S6A from Wong et al, NEJM 2021: Overall survival

Figure S6B from Wong et al, NEJM 2021: Transplant free survival

Other results of interest in CONFIRM:

in both the terlipressin and placebo arms, probability of HRS-1 reversal was much lower when SCr values were higher at randomisation,

the subgroup with SCr ≥5 mg/dL at enrollment did worse with terlipressin than with placebo (see discussion),

MAP increased by mean 8.5 mmHg at two hours post-terlipressin dose,

the mean MELD score decreased 3 points in the terlipressin group and 1 point in the placebo group, from baseline to the end of the trial,

amongst patients who were still alive post-liver transplant, 12/29 (41%) in the placebo group were still on RRT on day 90 after trial enrollment, whereas 9/46 (20%) in the terlipressin group still needed RRT.

Adverse events

The most common adverse events were abdominal pain, nausea and diarrhea. In the terlipressin arm, 12% of participants had an adverse event which led to discontinuation of the study drug, versus 5% in the placebo arm.

Those at high cardiovascular risk were excluded from the trial as the vasoconstrictor effects of terlipressin on the bowel, heart and skin are already well-described. Within the terlipressin group 4.5% of subjects had ischaemia-related adverse events versus zero in the placebo group.

A higher incidence of respiratory failure was reported in the terlipressin arm (14%) as compared to the placebo arm (5%). Within this, 17 patients died of respiratory failure in the terlipressin arm, whereas only 1 patient died in the placebo arm. The majority of these serious respiratory failure events in the terlipressin arm occurred early, with a median onset of 4.5 days (IQR 2-7 days).

Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Death due to respiratory failure in CONFIRM Study. Taken with minor modification from the FDA Briefing Document on Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Committee Meeting, July 15, 2020.

Discussion

Type 1 HRS is awful: untreated median survival is two weeks (Gines P. et al., Lancet, 2003). All credit to the investigators for recruiting to the largest ever RCT of a condition with the characteristics of rarity, lack of a definitive diagnostic test, vulnerable population, and high morbidity. Despite the predicted 90 day mortality of a population with baseline MELD score of 33 being over 70% (Mayo clinic, 2020), the care provided in this trial kept mortality to around 50% in both the treatment and placebo arms.

Mallinckrodt could be forgiven for confidently naming this the ‘CONFIRM’ trial. As mentioned above, guidelines in Europe already recommend terlipressin first line for HRS-1 when serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dl (without an upper creatinine threshold for when terlipressin should be initiated), as well as for acute variceal bleeding. RCTs have shown terlipressin to be superior to the midodrine and octreotide combination often already used in the USA and Canada (Cavallin M. et al, Hepatology, 2016), and meta-analysis from the same lead author of the CONFIRM trial indicate outcomes are probably equivalent to using norepinephrine (Wang H. et al., Medicine, 2018).

(As an aside…. think you recognise the sponsoring drug company’s name? You may recall Mallinckrodt from their $1.6 billion deal to settle lawsuits for their role in the US opioid crisis. Or from the $100 million fine paid to the US Federal Trade Commission when their subsidiary Questcor “took advantage of its monopoly to repeatedly raise the price of Acthar, from $40 per vial in 2001 to more than $34,000 per vial today – an 85,000 percent increase" - an issue which has also has an impact upon nephrology.)

And, now, in the CONFIRM trial the terlipressin arm had significantly greater reversal of HRS-1, and the signal for RRT avoidance looked good too. The positive late breaking abstract was welcomed. Third time’s a charm - now to get FDA approval, read the editorials with titles like “This trial CONFIRMs the role of terlipressin”, and re-draft the North American guidelines - right?

In case you missed the news in September, this is not what happened, and the FDA rejected terlipressin for a third time. The grim benefit of studying a condition with an appalling prognosis is that you can look past the rapidly achievable surrogate outcomes of benefit like improvement in serum creatinine to the things that really matter. The FDA had stated a wish to see “favourable trends” on clinical outcomes thought to be predicted by successfully treating HRS-1. No one is expecting a trial of HRS-1 to be powered to show statistically significant differences in liver transplant or death rates, but clinicians do want demonstration that the treatment is safe beyond just the shorter term primary outcome.

Essentially, the CONFIRM trial was never as much about terlipressin’s efficacy (we already know that it turns around more HRS-1 than placebo), but was more about the price the patients pay in adverse events for this pharmacological manipulation - and unfortunately the safety trends were disheartening.

Liver transplant

Transplantation is the exit strategy and definitive treatment. In the earlier, smaller OT-0401 and REVERSE studies, rates of liver transplant by day 90 were around 31% of patients in both the active treatment and the placebo groups. In CONFIRM, despite higher baseline rates of transplant listing in the terlipressin arm, the underwhelming result was fewer transplants occurring. Why is this?

Is it possible that terlipressin responders have an improved MELD score, and therefore will be disadvantaged by being put further down the transplant waiting list? In CONFIRM, over the course of treatment the mean MELD score decreased 3 points in the terlipressin group and 1 point in the placebo group: not a large difference, but the mean results will mask larger individual differences. Is it just due to chance? Or is it that terlipressin caused adverse events that prevented listing?

On the positive side, requirement for RRT post-liver transplant is a major risk factor for graft dysfunction and death (as one would expect), so the signal that fewer patients who received terlipressin needed ongoing RRT at the time the follow-up ended is a point in terlipressin’s favour.

Respiratory failure

The higher number of respiratory fatalities was not predicted from the previous smaller RCTs.

Can the cirrhotic pathophysiology, with very low systemic vascular resistance, really achieve enough increased afterload in response to terlipressin to drive respiratory failure? Maybe, and other causative links can be hypothesised as biologically plausible, such as via activation of V1a or V2 receptors in pulmonary vascular endothelium leading to deleterious changes in ventilation-perfusion matching. Either way, the numbers look concerning.

One other plausible contributing factor could be the 50% increase in volume of albumin received prior to starting the treatment period in CONFIRM when compared to the earlier REVERSE trail (though the mean amount of albumin received over the treatment period was actually remarkably similar in both). When the 3 RCTs in the series are pooled and participants stratified by albumin dose and treatment arm, it appears high prior albumin dose only associated with more respiratory events in the terlipressin group.

Table from FDA Briefing Document on Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Committee Meeting, July 15, 2020

The CONFIRM trial was double-blind and placebo controlled, and the volume of albumin was not dictated by a protocol, so it can be assumed that the doses given do represent the standard of care across the 60 enrolling sites. However albumin dosing may be more questioned now, after the simultaneous publishing ATTIRE study in NEJM.

ATTIRE showed that giving hospitalised patients with decompensated cirrhosis a median of 200g of 20% human albumin solution to target a serum level of >3g/dL (>30g/L) did not decrease short term infection, kidney dysfunction or death, but did increase pulmonary oedema and fluid overload events. It may be that adding terlipressin to high dose albumin just adds insult to the injury.

What are the terlipressin advocates saying?

Those who are hoping for terlipressin approval will say that the mean serum creatinine at enrollment of 3.5 mg/dL is too high, and we know that earlier treatment is associated with better outcomes. Maybe starting treatment at a lower creatinine threshold would have yielded different results.

There is also hope that continuous infusion is safer than the four times daily bolus regime used here, as has been indicated in one trial (Cavallin M. et al, Hepatology, 2016). Another fair comment would be to criticise liver transplant listing schemes based on MELD scores which do not adjust for reversal of HRS-1: these patients remain in a precarious scenario, but their MELD score based on current serum creatinine does not fully reflect this.

Were some of the trial population just too sick for terlipressin?

Mallinckrodt have published pooled data from the 385 patients in their 3 RCTs, focussing on the 77 patients with an enrollment creatinine ≥5 mg/dL ( ≥442 μmol/L). This group was much less likely to achieve reversal of HRS-1 whether in the treatment or placebo arm. The analysis demonstrated that by day 90 in the terlipressin arm 13/44 (30%) patients with baseline creatinine ≥5 mg/dL still alive, whereas 16/33 (49%) were still alive in the placebo arm, with median days of survival 12 days and 85 days respectively.

Overall survival up to 90 days by treatment group and baseline serum creatinine, pooled analysis (CONFIRM, REVERSE, OT-0401). Figure 30 in Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals Terlipressin Advisory Committee Briefing Document.

These observations led to Mallinckrodt proposing a “mitigation strategy” (section 8 at above link) to identify patients at high risk of harm and low risk of benefit who should not receive terlipressin. They state “for patients with SCr ≥5 mg/dL, treatment with terlipressin is not recommended”, though say this can be assessed on a case by case basis. They also stress the importance of stabilising any new or worsening dyspnea, fluid overload or pneumonia prior to giving terlipressin, and reducing to stopping terlipressin “if pneumonia occurs or progresses, or if pulmonary edema is severe”.

Despite Mallinckrodt saying they would undertake a comprehensive education program and enhanced pharmacovigilance activities post-authorisation, ultimately the FDA declined and stated that “based on the available data, the agency cannot approve the terlipressin NDA (new drug approval) in its current form, and requires more information to support a positive risk-benefit profile for terlipressin for patients with HRS-1”.

Conclusion

Predicted survival in HRS-1 is worse than most metastatic cancers, and effective prevention and treatment of HRS-1 remains a huge challenge. If hepatorenal syndrome is triggered by spontaneous bacterial peritonitis it becomes a complication of a complication of a complication (definitely too many complications in one sentence) of liver cirrhosis, clearly indicating patients have reached end stage organ failure. When you embark on therapy you need to know what you hope to achieve - if not improved mortality, then what?

Safety signals are not the statistically significant primary outcome, but the FDA has remained concerned after this trial. If you are in North America you shouldn’t hold your breath that you’ll be prescribing terlipressin anytime soon. In fact, the first guidelines this trial should influence are the European ones, whose authors need to seriously think if they can justify not having an upper creatinine threshold for terlipressin initiation in their HRS-1 recommendations, to limit terlipressin exposure in this population who appear to be better off with placebo instead.

The fact that the investigators have performed the largest ever trial looking at a treatment for this terrible condition must be applauded, and it has provided vital information we can use to help patients. Using long courses of high dose terlipressin in moderately advanced HRS-1 can increase your chances of decreasing serum creatinine and avoiding RRT beyond using albumin alone, which may buy vital time for select patients and keep some off RRT post-transplant. However, the addition of terlipressin is also evidently to the detriment of many patients, so this trial may just be a Pyrrhic victory. The job of sifting through this heterogeneous population to find out how narrow the therapeutic window is for terlipressin will have to continue.

Summary prepared by

Nephrology Attending,

Medical University of Białystok, Poland

and

Renal Registrar

Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK

NSMC Interns, Class of 2021