Should we call 2024 the Renaissance of nephrology? It was probably the richest year in RCTs in the nephrology world, reflected in the higher number of Late-Breaking Clinical Trials sessions at every big nephrology congress. Probably 1st place won’t surprise anyone; it was the anticipated FLOW of the year, but this Top 10 Nephrology Stories definitely includes some unexpected titles

The Top Nephrology Stories of 2021

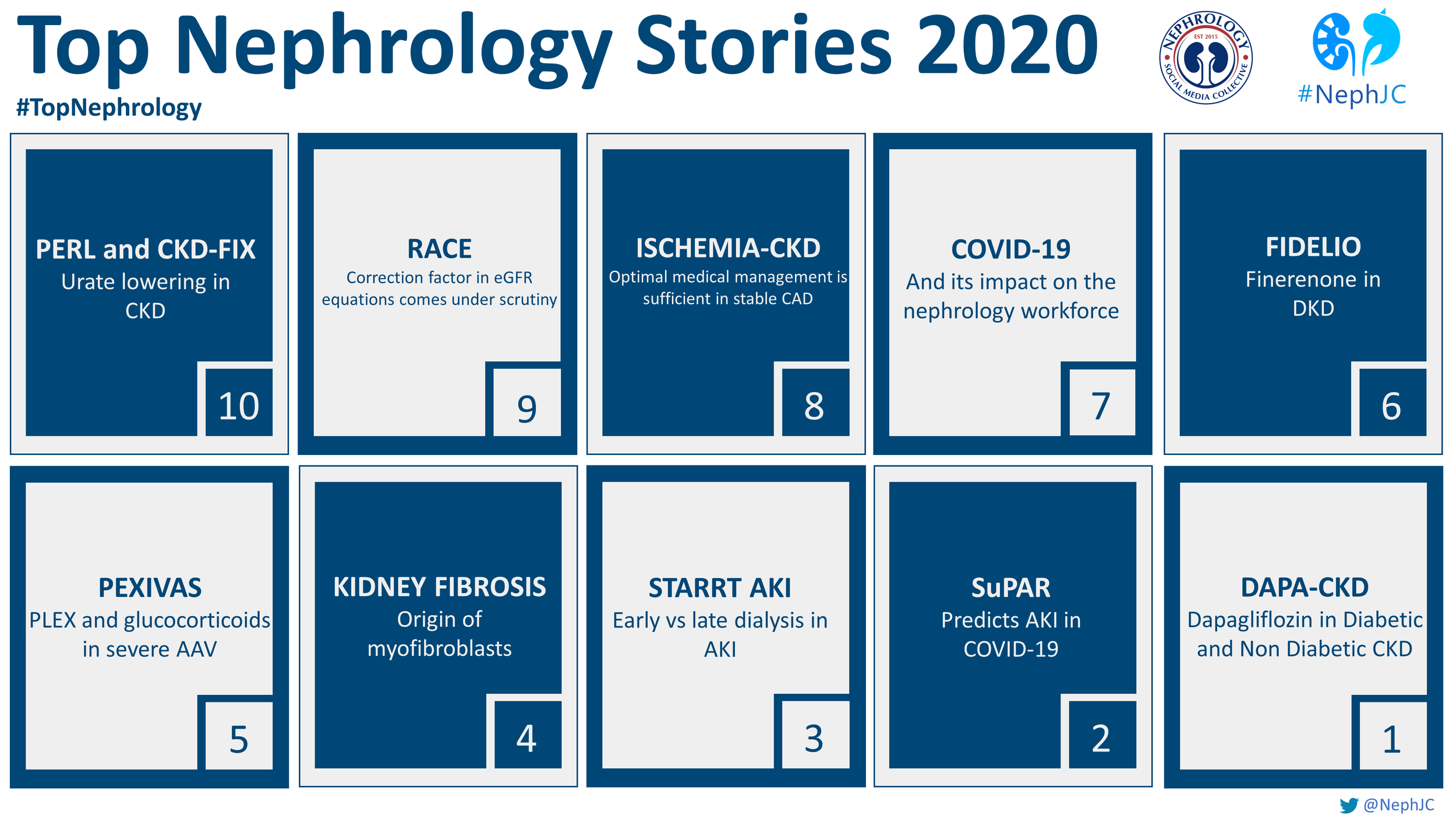

The Top Nephrology Stories of 2020

PEDIATRICS

COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, has rapidly become a global pandemic. This review aims to complement the other NephJC pages with a focus on how children with kidney disease are impacted by this pandemic. Our aim is to review what we know about COVID-19 as it pertains to kidney disease in kids.

Genetic Testing for Chronic Kidney Disease? Yes, please

Law 2. Outliers by Mukherjee, not Gladwell.

“Single patient anecdotes are often dismissed…But here, exactly such an anecdote had turned out to be a portal to a new scientific direction.”

In The Laws of Medicine by Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee, he describes a researcher who noticed an outlier in a clinical trial of a new drug for bladder cancer who responded to the treatment when others had not. Through genetic studies, they were able to find specific mutations in the tumor that conferred a higher likelihood of response, thus opening new avenues for therapy. He argues that you should pay attention to those outliers as much (or more) as you do the rest of the population, because they probably have something very valuable to teach us. I couldn’t agree more.

Pediatric nephrology is full of anecdotes that have informed nephrologists about the most basic kidney physiology. Congenital nephrotic syndrome was first described in the 1950s by Finnish nephrologists. While nephrologists were very familiar with typical minimal change nephrotic syndrome, these extremely rare children were different. They presented shortly after birth with massive proteinuria and died usually within the first year of life from infection. With improvements in supportive care, these children survived to kidney transplantation, however they still didn’t respond to our now standard treatment of steroids for nephrotic syndrome. It wasn’t until 1998, that the gene mutation responsible for this disorder was identified as nephrin (NPHS1), a slit diaphragm protein required for maintenance of the glomerular filtration barrier. This opened up a decade of fundamental research into the role of the podocyte in glomerular disease and helped to inform us about how the glomerular filtration barrier works.

In a less glomerulocentric view of the world (yes, I suppose there is such a thing), children with an unusual form of autosomal dominant hypertension were identified in the 1960s who had early onset disease with hypokalemia, suppressed renin and aldosterone, and responsiveness to triamterene but not spironolactone or dexamethasone. What on earth was going on in the tubule? It was long suspected that there was a defect in a sodium channel leading to salt and water retention, however the exact cause was elusive. Finally, in 1994, mutations in genes encoding the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) [SCNN1B, SCNN1G] were found to be the cause of Liddle syndrome, opening new doors into research on blood pressure homeostasis and sodium handling in the kidney.

Genetic kidney diseases are one of my favorite parts about pediatric nephrology. You can learn so much about normal physiology when just one little thing goes wrong. But, you have to recognize the outlier and start to think about how they got there. Is this a thing of the past? Have all the genetic causes of disease been discovered already? Of course not. Keep your eyes open for that zebra.

Commentary by Michelle Rheault, Minneapolis

The Lasting Effects of Childhood Kidney Diseases

A few of my favorite things-Alport syndrome 2017 year in review.

Is it weird to have a favorite disease? The one that you know better than most? The one where you can quote obscure articles from 1996 the way your nerdy cousin quotes original Star Wars dialogue?

“You came in that thing? You’re braver than I thought.”

The one that you can talk about to residents and fellows until their eyes glaze over? For me, that disease is Alport syndrome. My love affair started in fellowship, quite by accident. I did my required research time in the lab of Dr. Yoav Segal, an adult nephrologist who had just generated the first mouse model of X-linked Alport syndrome, at a time when you couldn’t just order a new transgenic mouse off the internet. I was fascinated by the fact that this very abnormal basement membrane worked perfectly normally at birth, then predictably thickened and led to mouse ESRD (i.e. death). What are the mechanisms that promote progression of CKD in Alport syndrome? What is the role of the other cells in the glomerular filtration barrier in disease progression? At that time, a diagnosis of Alport syndrome meant that you were invariably going to need dialysis or transplantation. Not only was there no cure, but our best doctor response was: “I’m afraid there’s nothing we can offer.” A lot has changed since then including recognition that ACE inhibitors can slow progression and insights into the disease pathogenesis. Although I’m not in the lab anymore, I still keep very close track of the field and thought I would share my top 10 Alport Syndrome Advances and News of 2017.

Twitter moment: https://twitter.com/i/moments/94594518026736025

Although a lot of worthy papers and events this year, my Number One was the 2017 International Alport Syndrome workshop in Glasgow sponsored by AlportUK and organized by Dr. Rachel Lennon (@RLWczyk). This is the 3rd meeting of this group of basic science and clinical researchers, adult and pediatric nephrologists, patients, pharma, and geneticists who get together to share their work, find new ways to collaborate, and work to set a coherent research agenda for the field. This is a model of how research should be done. We shouldn’t be hiding our work from others and focused on who can publish first. We should be working together to advance the field as quickly as possible for the benefit of patients with this disease. They don’t care how many publications I have on my CV, but they do care if they can delay dialysis from their early 20s to their 30s or 40s or hopefully someday cure the disease entirely.

I hope none of the other renal diseases are jealous, but Alport syndrome will always be my favorite. Looking forward to what 2018 will bring!