#NephJC Chat

Tuesday Sep, 6th, 2022 at 9 pm

Wednesday Sep 7th, 2022, at 9 pm IST and 3:30 pm GMT

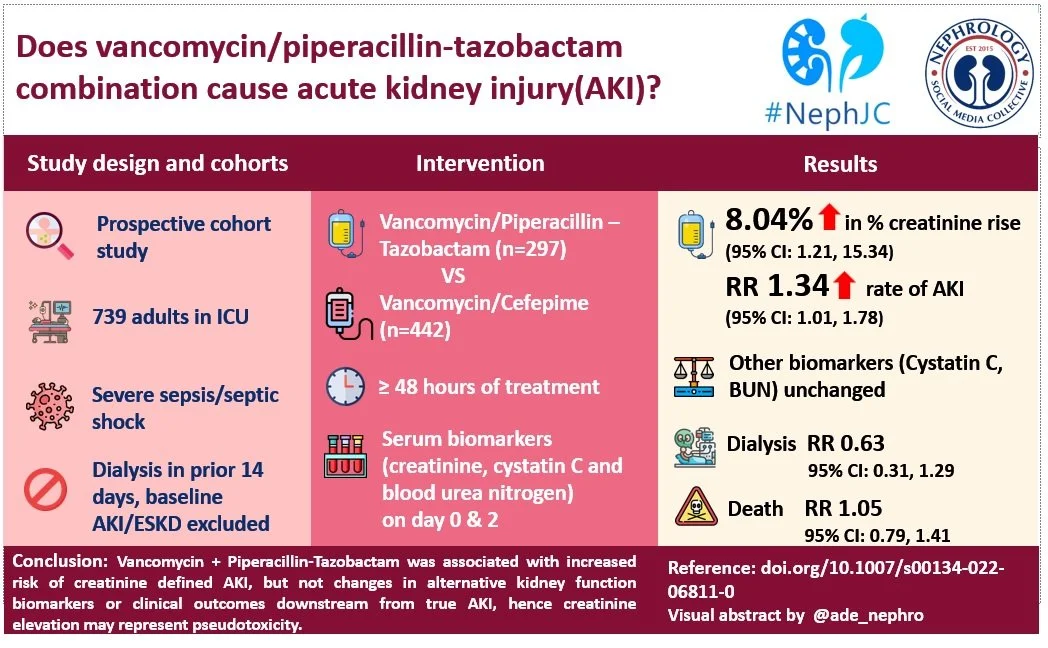

Intensive Care Med 2022 Jul 14. doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06811-0. Online ahead of print.

Association of vancomycin plus piperacillin-tazobactam with early changes in creatinine versus cystatin C in critically ill adults: a prospective cohort study

Todd A Miano 1 2 3, Sean Hennessy, Wei Yang, Thomas G Dunn 7, Ariel R Weisman 7, Oluwatosin Oniyide 7, Roseline S Agyekum, Alexandra P Turner 7, Caroline A G Ittner 7, Brian J Anderson, F Perry Wilson 8, Raymond Townsend 9, John P Reilly, Heather M Giannini, Christopher V Cosgriff, Tiffanie K Jones, Nuala J Meyer, Michael G S Shashaty # 6 7

DOI: 10.1007/s00134-022-06811-0

PMID: 35833959

Introduction

The vancomycin (VN) and piperacillin-tazobactam (PT) cocktail has been a popular broad spectrum antibiotic combination for acutely ill patients hospitalized for sepsis. In 2016, an article examining antibiotic use in over a million admissions found that VN and PT were the two most used antibiotics.

Around 2011, reports of increased rates of acute kidney injury (AKI) after VN+PT use compared to other antibiotics combinations began to appear in the medical literature (Covert et al, J Clin Pharm Ther 2020). Of course, this combination was often used in very sick patients who were at high risk of AKI from sepsis regardless, so it took some time (with controlled studies such as this one NephJC reviewed in 2016) to convince people of the signal. Since then nearly 50 observational studies and periodic meta-analyses have supported the association of VN+PT with AKI. Some large health systems have already implemented protocols to avoid the combination under antibiotic stewardship programs due to fear of AKI.

But is this reasonable? Avoidance of this ‘workhorse’ combination reduces the options available to treat life threatening infections. However, if the combination is indeed nephrotoxic, use of VN+PT could increase morbidity and mortality.

Vancomycin nephrotoxicity

The onset of nephrotoxicity with vancomycin typically occurs after 4-8 days of exposure. Vancomycin can alter mitochondrial function and induce oxidative stress, release cytochrome-c, and activate the caspase pathway leading to cellular stress and apoptosis. When patients are biopsied, the most common finding is acute tubular necrosis. Some patients have obstructive tubular casts, and others have findings consistent with acute interstitial nephritis. The casts are composed of non-crystal nanospheric vancomycin aggregates entangled with uromodulin. Vancomycin also suppresses the expression of organic anion transporters, OAT1 and OAT3, inhibiting secretion of creatinine. This contributes to the steep rise of creatinine sometimes observed with vancomycin associated AKI (Velez et al, Nephron 2018, a case series which famously began on ASN communities).

Piperacillin-Tazobactam nephrotoxicity

Similar to vancomycin, acute interstitial nephritis can occur with piperacillin + tazobactam, but is rare. Both are substrates for organic anion transporters OAT 1, OAT 3 which have been shown to be involved in the tubular handling of creatinine (see figure 1 below). So while there is no disputing that addition of PT raises creatinine as the evidence suggests (Bellos et al, Clin Microbiol Infect 2020), this elevation in creatinine may represent pseudo-toxicity, akin to the more familiar effect of trimethoprim inhibiting tubular secretion of creatinine, rather than true injury. The inhibition of transport may in fact reduce the entry of nephrotoxic drugs into the proximal tubules and exert a nephroprotective effect when administered in addition to other antibiotics. Competitive inhibition of creatinine secretion and VN-mediated transporter suppression are a plausible mechanism of the increased creatinine repeatedly seen with VN+PT use.

Figure 1: Both Piperacillin and tazobactam (PT) are substrates for organic anion transporters(OAT) that mediate creatinine transit. Vancomycin(VN) suppresses the expression of these pumps.

So how does one tease out if VN+PT is truly nephrotoxic?

At this stage the evidence is mixed. The best evidence pointing away from nephro-toxicity of VN+PT is a study of 1200 critically ill patients from Denmark (Jensen et al, BMJ Open 2012) demonstrating a rapid decline in creatinine upon antibiotic discontinuation which is not characteristic of the slower declines typically seen in acute kidney injury. On the other hand, of the many studies that consistently report the association of VN+PT and AKI (Bellos I et al, Clin Microbiol Infect 2020), a large study by Côté et al showed that patients receiving PT did not have a higher rate of KRT at 7-days but did have a higher rate of AKI at 30-days. The bulk of the accumulated data have only used serum creatinine to assess nephrotoxicity. However, one urinary biomarker study of the VN+PT combination (Kane-Gill et al, Drug Safety 2019) measuring cell-cycle arrest biomarkers- urinary tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 (TIMP-2) and insulin-like growth factor binding-protein 7 (IGFBP7), whose product identifies renal tubular epithelial cell stress, did find the highest product values with VN+PT, compared to either agent used alone.

Using insights from renal tubular handling of biomarkers may assist in identifying mechanisms of tubular toxicity. Anywhere from 10 to 40% of excreted creatinine is cleared by proximal tubule secretion and this can rise to 60% in CKD. (Bauer et al, AJKD 1982) Cystatin-C (Cys-C) is a low molecular weight protein (13-kDa), produced at a constant rate by all nucleated cells. It is freely filtered at the glomerulus and is not secreted from the tubule (NephJC coverage). Proximal tubular cells reabsorb and catabolize it, so that normally no Cys-C is excreted in the urine. This is not influenced by age, sex, diet, or muscle mass. The half-life of Cys-C is only 2 hours compared to 4 hours for creatinine, so Cys-C can detect changes in GFR faster than creatinine. (Sjostrom et al, Clin Nephrol 2004)

The study we are discussing today from Miano et al is the first to use Cys-C to challenge the accepted notion that VN+PT is nephrotoxic.

The Study

Design

This study was a part of the MESSI (Molecular Epidemiology of SepSis in the ICU) project, which is an ongoing prospective observational study designed for the intensive care unit, enrolling patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. It uses the previous Sepsis-2 criteria for patient inclusion.

Inclusion criteria

This study included participants treated with Vancomycin + Piperacillin-Tazobactam (VN+PT) or Vancomycin + Cefepime (VN+CP) for 48 hours or more, with each drug initiated within 48 hours of

ICU admission. Cefepime was chosen as a comparator since it is also amongst the favored combinations for empiric treatment and has been shown to have lower risk of AKI compared to VN+PT (Navalkele et al, Clin Inf Dis 2017).

Exclusion criteria

1. End stage renal disease

2. Dialysis 14 days before the index date

3. Baseline AKI (index creatinine > 1.5 times baseline)

(Index creatinine was defined as the last value of creatinine available before the index date, and baseline creatinine was defined as the average of outpatient or hospital discharge creatinine values 365 days to 7 days before hospital admission. When these values were unavailable, the lowest creatinine within 7 days prior to ICU admission was considered as baseline. Index date was defined as the date and time when combined antibiotic therapy was started)

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were Creatinine and Cystatin-C measures at index and day two (48-72 hours) after initiation of antibiotic combination.

Secondary outcomes were

Creatinine-defined AKI through day 14

Need for kidney replacement therapy

30-day mortality

Outcomes were modeled using IPTW linear regression to adjust for confounding factors.

Results

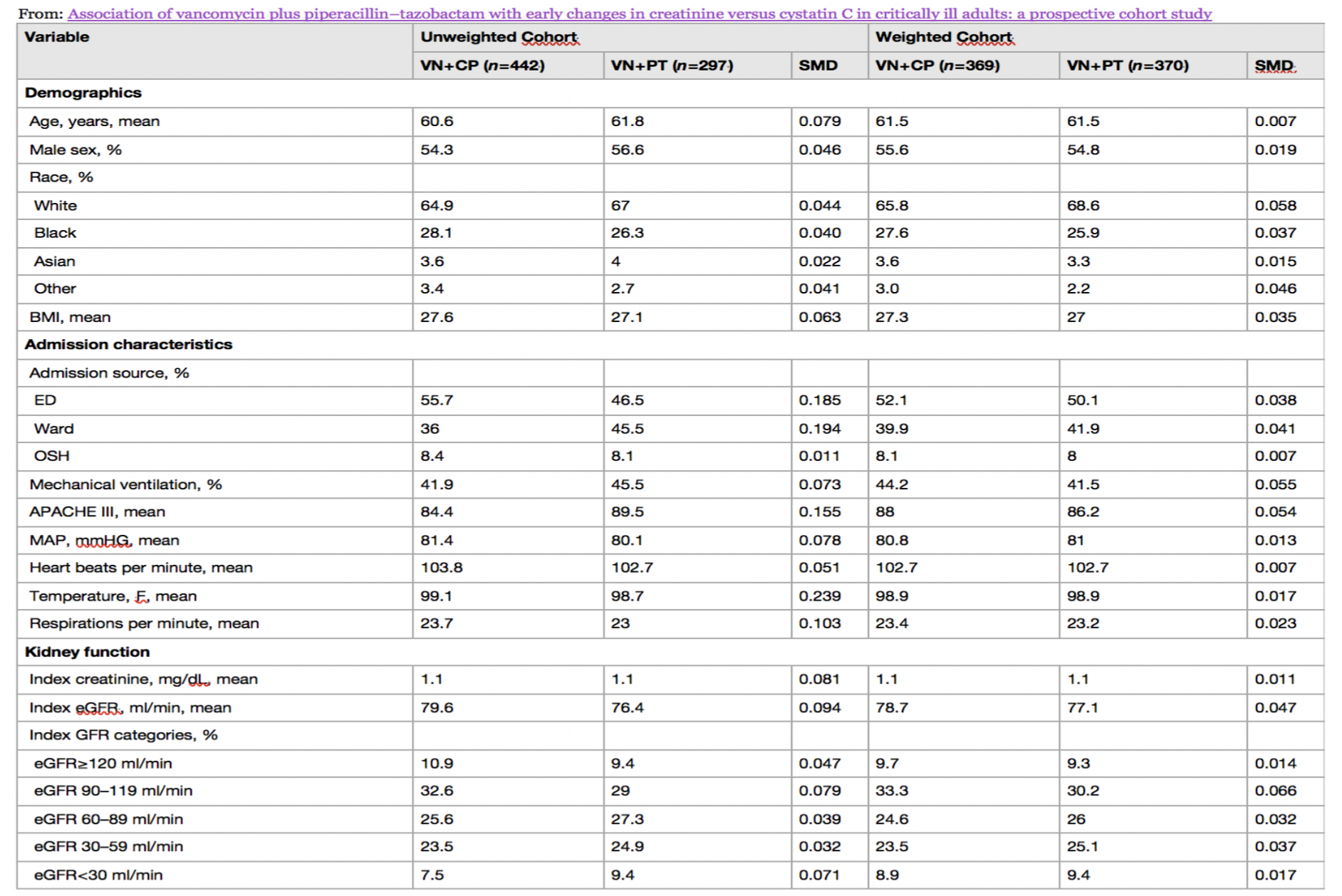

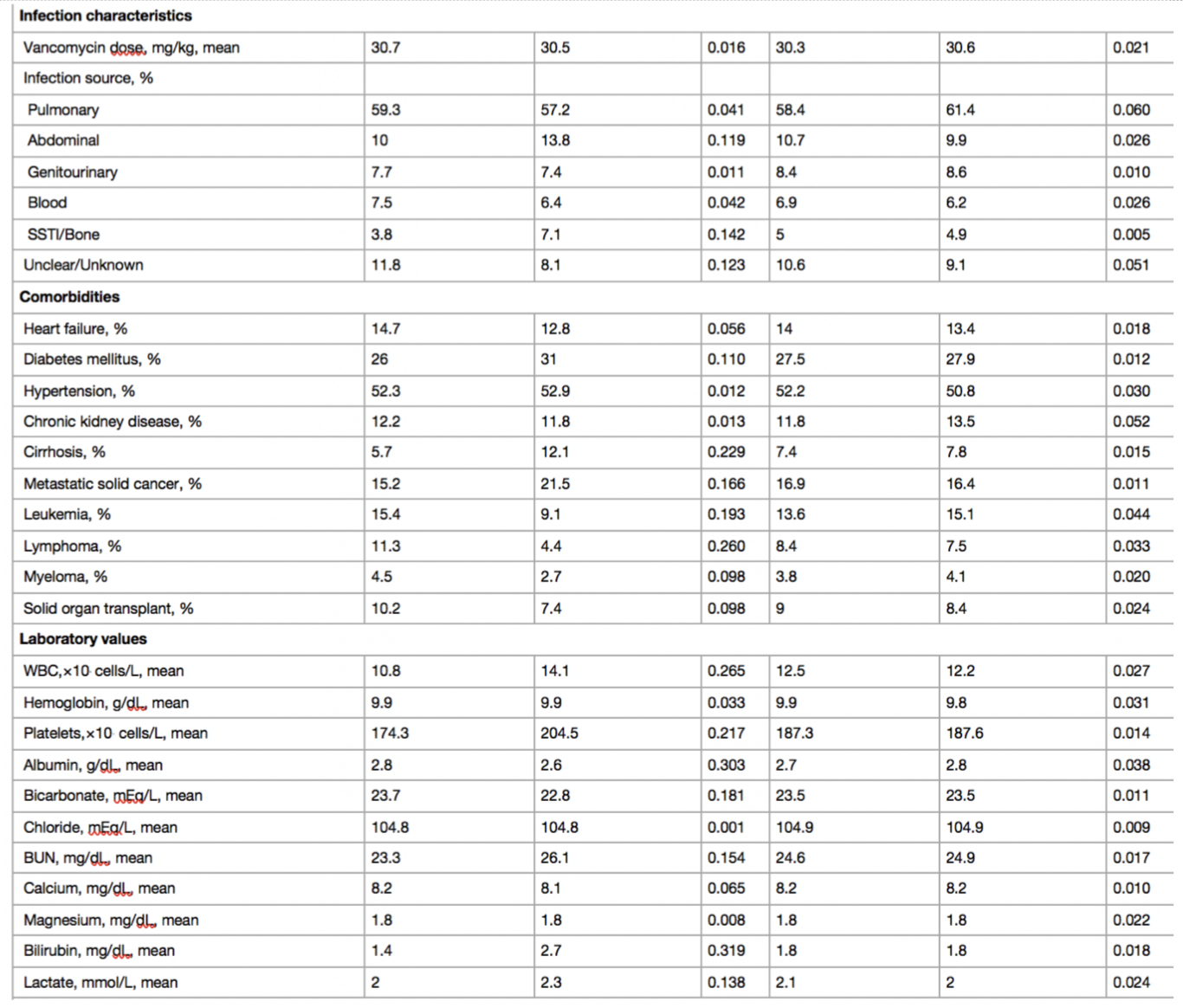

The study included 739 patients : VN+PT, n=297 and VN+CP, n=442. 192 had cystatin-c measurements. See Figure below. Creatinine and BUN values were obtained from the EHR. Cystatin-C values were obtained from frozen plasma samples taken from residual citrated samples from the ED or ICU collections.

Figure: Study sample selected from patients enrolled in MESSI

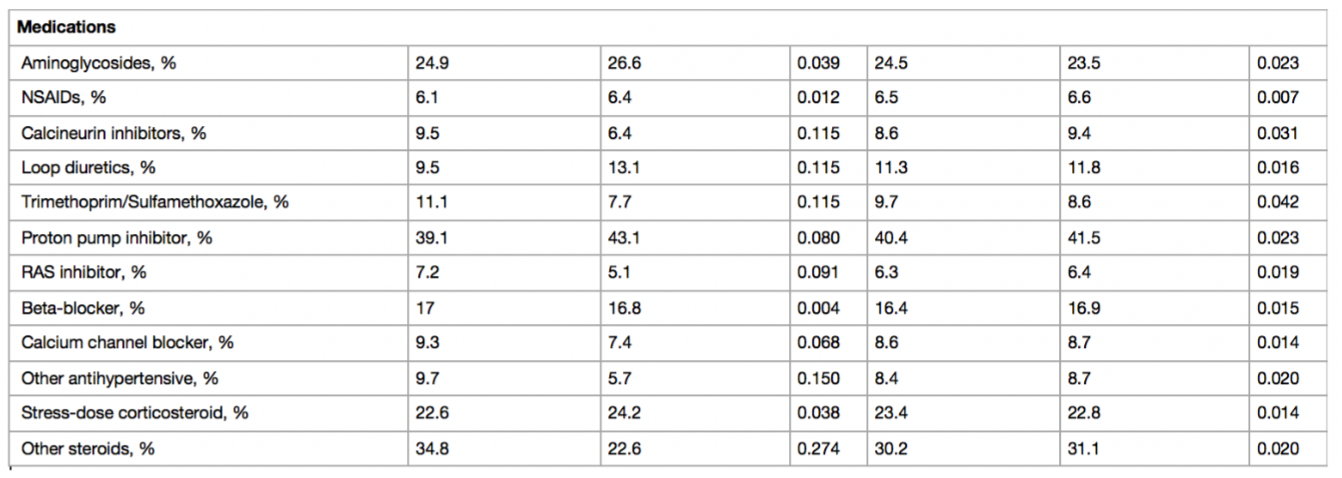

Baseline characteristics before and after weighing in antibiotics cohorts as shown in Table 1. Before weighting, VN+PT patients had higher severity of illness score, lower baseline GFR, higher lactate and more frequent diabetes mellitus and cirrhosis. In the Cys-C sub-cohort, there was minor residual imbalance in respiratory rate, hypertension, cancer, and solid organ transplant. Medications, laboratory values, and dialysis orders were obtained via EHR. Concomitant medications and lab variables were assessed. Supplemental table S2 details the baseline characteristics for the Cys-C sub-cohort.

Table 1: SMD standardized mean difference, BMI body mass index, ED emergency department, OSH outside hospital, APACHE Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, MAP mean arterial pressure, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, SSTI skin and soft tissue infection, WBC white blood cell, BUN blood urea nitrogen, NSAID nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug, RAS renin–angiotensin system, VN + PT vancomycin + piperacillin–tazobactam, VN + CP vancomycin + cefepime

Table S2: Baseline characteristics before and after weighting in Cystatin C subcohort

Kidney function biomarkers at day 2

Firstly, with respect to biomarker levels at day 2, the VN+PT was found to have higher average creatinine concentrations, but lower average Cys-C and similar BUN concentrations (Table 2). Frequency of increase in biomarker concentrations by 50% or more at day 2 was higher for creatinine and similar for Cys-C and BUN (Table 3).

Table 2: Percentage difference in kidney function biomarker concentrations at day two.

Table 3: Rates of ≥ 50% increases of kidney function biomarkers at day two.

Both the Cys-C: creatinine ratio and BUN:creatinine ratio were significantly lower in the VN+PT group vs the VN+CP group, showing that creatinine increased to a greater extent than Cys-C or BUN by day two. (Supplemental Table S7)

Clinical outcomes

Clinical outcomes studied are shown in table 4. The VN+PT cohort showed significantly higher rate of rise in creatinine, as reflected in higher rates for the parameter ‘KDIGO defined AKI’, a term used by the authors to indicate AKI by creatinine criteria only, since urine output data wasn’t included in the study. KDIGO defined AKI occurred at higher rates for the VN+PT cohort at both 7 and 14 days. The development of AKI with VN+PT was seen in the first one or two days. After that the rates of AKI seemed about the same between groups. (Supplemental Figure S4).

Figure S4: The figure shows the time to acute kidney injury defined according to the KDIGO creatinine criteria. Time to AKI was significantly shorter for the VN+PT group vs. VN+CP group (log rank test, p<0.001)

Also important to note is that the association with AKI was attenuated and non-significant when analyzed for stage 2 or higher AKI. Also, in continuum, the rate of AKI requiring dialysis at 14 days and mortality at 30 days was not different in both the groups, after weighting and accounting for baseline imbalances. Authors also report that results were minimally changed by propensity score trimming or adjustment for the calendar year. Steroid use did not affect Cys-C measurements.

Discussion

Strength of the study

This is the first study of VN+PT to employ Cys-C as an alternative to creatinine.

Since Cys-C does not undergo tubular secretion it is an insightful choice to examine the potential of pseudo-nephrotoxicity from loss of creatinine secretion.

Use of VN+PT was associated with increased creatinine at day two and increased Cr defined AKI at day 14 but there were no associated increases in Cys-C or increases in need for kidney replacement therapy or mortality. Similarly, use of VN+PT was not associated with changes in BUN, another biomarker which does not undergo tubular secretion.

The additional finding that the AKI occurred early after starting the antibiotics is consistent with creatinine rising due to inhibition of proximal tubule creatinine secretion.

Limitations

Like any other study evaluating AKI due to drug toxicity in critically ill patients, the study design is vulnerable to confounding due to presence of other factors causative of AKI. The authors also admit to issues of missing data. Though appropriate statistical methods were utilized, and the differing results obtained in the unadjusted versus the weighted cohort of both antibiotic group at large and Cys-C group as a subset, cannot be downplayed.

A systematic review (Luther et al, CCM 2018) reported the observed range for mean times to AKI with VN+PT as 2.3-5.67 days. Côté et al have also reported a correlation of VN+PT with late occurring AKI requiring kidney replacement therapy at the other end of the spectrum. In this context, whether the choice of 48 hours as the defining window for AKI is adequate remains a persistent concern.

Use of BUN has limitations, in that a rise in BUN can reflect processes other than kidney injury (e.g. gastrointestinal bleeding, volume depletion, steroids, sepsis, etc). Similarly, cystatin-C concentrations are affected by body mass index, corticosteroids, thyroid disease, cancer, diabetes, and solid organ transplant. Many of these are common comorbidities found in sick patients with sepsis, hence results from use of this biomarker must be interpreted with caution. Indeed >50% of patients in this study were exposed to steroids. Additionally, only a subset of patients within the cohort had measurements of Cys-C within the timing window for inclusion, and 192 patients with reassuring Cys-C measurements from a single center may not be enough to safely call the nephrotoxicity a myth. The excellent editorial by Patrick Murray, et. al rightly points out that most previous studies showing AKI association included thousands of patients.

The study may have benefitted from the use of other kidney injury biomarkers as well. Urinary sediment analysis also has a potential to serve as a biomarker for AKI, and is something that can be included in the observations without a major burden on the methodology (see NephJC discussion of a urinalysis study).

Some other points that were not evaluated in this study, but are important clinical considerations in day-to-day practice, include the effect of dilution of biomarkers during initial fluid resuscitation and the absence of urine output data.

Overall this study is a chink in the narrative of VN+PT nephrotoxicity, but given the limitations above we are not yet at the point of it calling this a medical reversal. In an interview about the study Miano says it brings the issue back to equipoise, which seems about right. It is hoped that large, randomized studies on the question, such as the Effect of Antibiotic Choice on ReNal Outcomes (ACORN) trial, will give us the definitive answer in the near future.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations, Miano et al stands out as a well designed experiment to test whether the VN+PT combination is nephrotoxic or merely only responsible for hypercreatinaemia. It observed the rise in creatinine in the first 48 hour period of use, but without corresponding rises in Cys-C or BUN, and with no increase KRT or mortality. Though far from definitive, this study will somewhat reassure physicians faced with a patient they feel would benefit from this antibiotic combination.

Summary prepared by

Sayali Thakare

Nephrologist, KEM Hospital, Mumbai

Kavitha Ramaswamy

Nephrologist, Philadelphia

NSMC Interns Class of 2022

Reviewed by Jamie Willows, Priti Meena,

Jade Teakell, Joel Topf, & Swapnil Hiremath