#NephJC Chat

Tuesday Oct 20 , 2020 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday Oct 21 , 2020 9 pm IST

Wednesday Oct 21 , 2020 9 pm BST

Kidney Int 2020 Oct;98(4):839-848. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.06.024. Epub 2020 Jul 10.

Executive summary of the 2020 KDIGO Diabetes Management in CKD Guideline: evidence-based advances in monitoring and treatment

Ian H de Boer, M Luiza Caramori, Juliana C N Chan, Hiddo J L Heerspink, Clint Hurst, Kamlesh Khunti, Adrian Liew, Erin D Michos, Sankar D Navaneethan, Wasiu A Olowu, Tami Sadusky, Nikhil Tandon, Katherine R Tuttle, Christoph Wanner, Katy G Wilkens, Sophia Zoungas, Lyubov Lytvyn, Jonathan C Craig, David J Tunnicliffe, Martin Howell, Marcello Tonelli, Michael Cheung, Amy Earley, Peter Rossing

PMID: 32653403

Full Guideline Text: PDF (free)

KDIGO page with links to videos, more resources

Introduction

This time, KDIGO has brought us their first guidelines on diabetes management in chronic kidney disease (CKD), where we find recommendations about comprehensive care, glycemic monitoring and targets, lifestyle and antihyperglycemic interventions, and approaches to self-management and optimal models of care. What led to a new diabetes in CKD guideline? Like many others, these typically follow a ‘controversies’ conference - in this case one from 2015 (Perkovic et al, Kidney Int 2016). Let’s delve into the methods behind the KDIGO guidelines.

Methods

These guidelines include recommendations for type 1 and 2 diabetes, and all stages of CKD (dialysis and kidney transplant recipients). They are divided in five chapters, each one of them is divided in recommendations and practice points. What’s the difference?

Practice points are consensus statements about a specific aspect of care and represent the expert judgment of the guideline work group, but may also be based on limited evidence (not graded for strength or quality of evidence). One might think of them as the 2D recommendations scattered across previous KDIGO guidelines.

Recommendations are based on a larger quantity of evidence. KDIGO guidelines continue to use GRADE methodology (Guyatt et al, BMJ 2008).

The work group consisted of multidisciplinary, experienced and dedicated members with deep experience in the subject, with two of the members being patients with diabetes and CKD, to keep the guideline relevant and patient-centered.

Funding: The KDIGO guidelines are typically funded by KDIGO itself and not directly from pharma. On the other hand, note that their strategic partners include most drug companies involved in diabetes management and more. Similarly, apart from the two patients, the dietitian and a couple of doctors, most workgroup members do have disclosures (see page 101 onwards of main document) to companies whose products are being discussed below. Thus, unlike some other organizations (eg USPSTF) disclosures do not prevent workgroup membership.

The Guidelines

Overall, there are 12 recommendation statements, and several practice points.

There are

One 1A (guess which one)

Three 1B

Three 1C

Two 1D

No 2A

One 2B

Two 2C recommendations

There are no 2D recommendations, because these are replaced by many practice points.

There are 5 chapters, as detailed below. Apart from the quality of evidence, each section also has sections on

Values and preferences

Resource implications

Considerations for implementation

Research recommendations

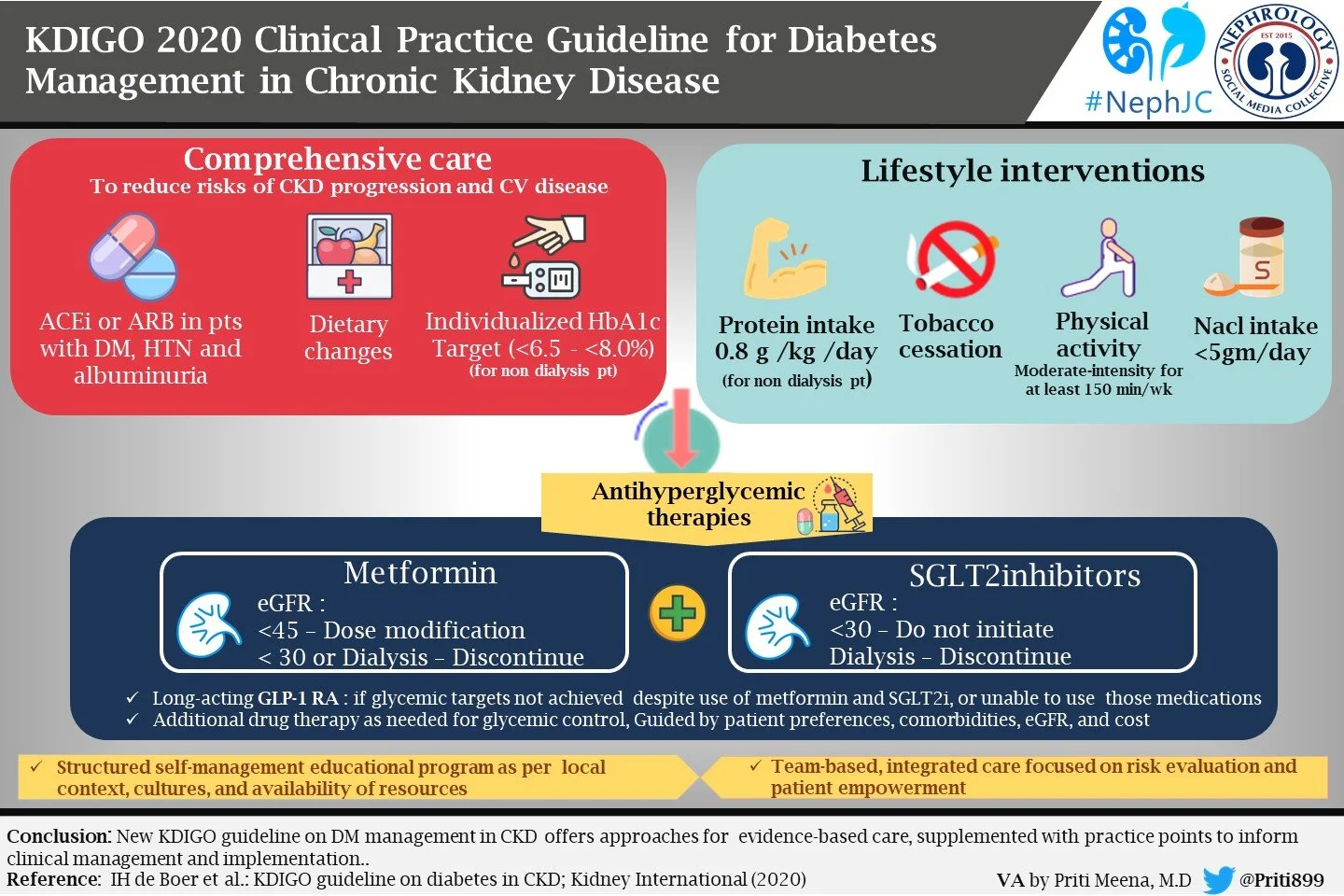

Chapter 1: Comprehensive care in patients with diabetes and CKD

Management of CKD in diabetes can be challenging and complex, and a multidisciplinary team should be involved (doctors, nurses, dietitians, educators, etc). Patient participation is important for self-management and to participate in shared decision-making regarding the management plan. (Practice point).

They also provide common sense advice that patients with diabetes and CKD should be treated with a comprehensive strategy to reduce risks of kidney disease progression and cardiovascular disease:

Adjust type and doses of medications according to kidney function.

Management of anemia, bone and mineral disorders, fluid and electrolyte disturbances.

Then comes a recommendation

We recommend that treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) be initiated in patients with diabetes, hypertension, and albuminuria, and that these medications be titrated to the highest approved dose that is tolerated (1B).

Since the presence of albuminuria is related to increased kidney and cardiovascular risk, renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockade is recommended in patients with diabetes, hypertension, and albuminuria. Trials like IRMA-2 (Parving et al, NEJM 2001) demonstrate a reduced risk of progression of CKD in patients with diabetes and moderately increased albuminuria (30-300mg/day) using RAS blockade. Also IDNT (Lewis et al, NEJM 2001) and RENAAL (Brenner et al, NEJM 2001) found beneficial effects in patients with severely increased albuminuria. The overall summary is provided in this Cochrane review (Strippoli et al, CDSR, 2006). Note that there is no preference for ACEi over ARBs. The workgroup considered the two equivalent.

There are subsequent practice points on how to manage ACEi/ARB in these patients. Use of ACEi/ARB in normotensive diabetes is a practice point and not a recommendation based on the lower quality of evidence.

There is some interesting advice on how to start and when to stop ACEi/ARB: not to stop for hyperkalemia (do other things like add diuretics, bicarb, or GI exchange resins); to consider stopping them on the basis of the (non-evidence based, see NephJC discussion) 30% rule; and to reduce/stop if uncontrolled hyperkalemia or to control uremic symptoms when GFR < 15. Guess we have to wait for STOPACEi (Bhandari et al, NDT 2016) to see if that final point is accurate.

Fig 4 from KDIGO Guidellines

A very strange practice point is to avoid dual RAS blockade, ie ACEi + ARB (or direct renin inhibitor for aliskerin fans) combination. Why only a practice point only, one must wonder given the results of ONTARGET (Mann et al, Lancet 2008) and VA-NEPHRON-D (Fried et al, NEJM 2013) showing a clear higher risk of AKI and hyperkalemia? Shouldn’t this be a 1A recommendation?

As for the forgotten A of the RAAS system, mineralocorticoid antagonists are also relegated to a practice point since they control hypertension, but can cause hyperkalemia or GFR decline. (2 days until the FIDELIO-DKD [Bakris et al, 2019] results potentially demolish this. Also see this systematic review [Currie et al, BMC Nephrology 2016] to note spironolactone addition to RAS blockade reduces not just BP, but proteinuria).

Missing in all this is what should be a BP target when you use RAS blockade, or any discussion about RAS blockade versus other BP lowering drugs in this setting. Look for that in the upcoming KDIGO BP in CKD guidelines, we surmise?

Chapter 1 then ends with a recommendation on...smoking cessation

We recommend advising patients with diabetes and CKD who use tobacco to quit using tobacco products (1D).

This makes it to a 1D recommendation based on a trial of a fascinating crossover (yes, it means what you think it does) of 25 patients, of whom only 15 were diabetic, with outcomes of BP and proteinuria (Sawicki et al, J Int Med 1996). Interesting that this makes it to a recommendation. We are not part of Big Tobacco, so we’ll let this pass. Though there is a sentence on e-cigarettes in the small print, vaping does not rise up to even become a practice point.

Chapter 2: Glycemic monitoring and targets in patients with diabetes and CKD

This section has 2 recommendations (both 1C) and a host of practice points.

On Glycemic monitoring,

We recommend using hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) to monitor glycemic control in patients with diabetes and CKD (1C).

and on glycemic targets,

We recommend an individualized HbA1c target ranging from <6.5% to <8.0% in patients with diabetes and CKD not treated with dialysis (1C).

HbA1c may seem like a simple recommendation - but isn’t. The effect of lower red cell life span at lower GFR (as well as potentially any interference from carbamylated Hb from urea?) makes it correlate with blood glucose less reliably. Unfortunately, the alternatives, glycated albumin and fructosamine also perform poorly. Hence, despite a discussion in the ‘values and preference’ section that some might prefer continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), the workgroups gives the nod to HbA1c. Hence several practice points do follow on the role of CGM and self monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) with a table showing that these may be preferable in CKD stages 4 and 5 and when risk of hypoglycemia is higher. Additionally, when CGM/SMBG is not possible, they suggest drugs with a lower risk of hypoglycemia be used (eg metformin, SGLT2i, GLP1 agonists and DPP4 inhibitors).

What about the target HbA1c, at a 1C rating?

The quality of evidence here that targeting lower glucose is beneficial is rather poor, with heterogeneity, indirectness, and other risks of bias. Hence note that this is letting people pick a HbA1c target, with a < 8 for certain groups and < 6.5 for others, with a (opinion based) figure provided for choice.

Fig 9 from KDIGO Guidelines

The factors that should be taken into account to pursue a specific HbA1C level include patient preferences, severity of CKD, presence of comorbidities, life expectancy, hypoglycemia burden, choice of antihyperglycemic agent, and available resources.

Chapter 3: Lifestyle interventions in patients with diabetes and CKD

It may not come as a surprise that these are the weakest recommendations in the entire document, given that these mostly deal with diet and nutrition, an area where confounded observational studies dwarf the pitiful (mostly negative) trials. One might be tempted to compare these with the equally interesting K/DOQI guidelines on nutrition that came out a few months ago (Ikizler et al, AJKD 2020).

It starts off with an fascinating practice point, favoring veganism: diet should be individualized and balanced with high content of vegetable, fruits, whole grain, fiber, legumes, plant-based proteins, unsaturated fats, and nuts; and lower content in processed meats, refined carbohydrates and sweetened beverages. No one tell the keto community. We have visited the red meat part of this before (NephJC discussion of Lew et al.).

This is followed by two 2C recommendations

We suggest maintaining a protein intake of 0.8 g protein/kg)/d for those with diabetes and CKD not treated with dialysis (2C).

On the amount of proteins recommended in these guidelines, they suggest (‘recommend’ becomes a ‘suggest’ at this level of evidence) a very precise intake of 0.8g/kg/d in patients with diabetes and CKD. Lower dietary protein intake has been hypothesized but never proven to reduce glomerular hyperfiltration and slow progression of CKD, however in patients with diabetes, limiting protein intake below 0.8g/kg/d can be translated into a decreased caloric content, significant weight loss and quality of life. Malnutrition from protein and calorie deficit is possible. But why this amount and not more? The popular low carb movement usually results in higher protein intake. Theoretical concerns aside, good trial evidence supporting this recommendation is not there. After discussing the poor quality of evidence, the workgroup uses the WHO recommendation (which is meant for all of humanity) as a shield to justify their 2C statement.

Fortunately, this is followed by a practice point, lifting these protein restrictions for dialysis patients: Patients treated with hemodialysis, and particularly peritoneal dialysis, should consume between 1.0 and 1.2 g protein/kg/d.

Then comes another 2C suggestion:

We suggest that sodium intake be <2 g of sodium per day (or <90 mmol of sodium per day, or <5 g of sodium chloride per day) in patients with diabetes and CKD (2C).

We have strong evidence that lowering sodium intake lowers BP (eg DASH and other trials) but no such luck when it comes to prevention of clinical outcomes (see NephJC discussion of PURE studies). Hence this becomes a 2C suggestion. The ‘values and preference’ section is especially well written, discussing cost, cultural choice, and access issues in this regard.

Physical activity

We recommend that patients with diabetes and CKD be advised to undertake moderate-intensity physical activity for a cumulative duration of at least 150 minutes per week, or to a level compatible with their cardiovascular and physical tolerance (1D).

Fig 17 from KDIGO Guidelines

Patients with diabetes and CKD are advised to undertake moderate-intensity physical activity for a cumulative duration of at least 150 minutes per week, or to a level compatible with their cardiovascular and physical tolerance. The absence of good evidence doesn’t stop this climbing from a 2C for the nutrition guidelines to a 1D. There are some trials, but unblinded with high risk of bias. Plus some observational studies. This does not have to be structured exercise funded by Big Gym; walking, biking, running is considered physical activity. Not being sedentary is the key. The practice points also deal with fall prevention which seems important.

Chapter 4: Antihyperglycemic therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and CKD

This is where things get even more exciting. Should we add SGLT2i to the drinking water? Are they first line or is it metformin (as the ADA does, but not the EASD which has elevated SGLT2i to first line)?

Let’s dive in.

The section starts off with a few practice points:

Glycemic management for patients with T2D and CKD should include lifestyle therapy, first-line treatment with metformin and a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor (SGLT2i), and additional drug therapy as needed for glycemic control (Practice point 4.1)

Figure 18 from KDIGO guidelines

Most patients with T2D, CKD, and eGFR ≥30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 would benefit from treatment with both metformin and an SGLT2i. (Practice point 4.2)

Patient preferences, comorbidities, eGFR, and cost should guide selection of additional drugs to manage glycemia, when needed, with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) generally preferred (Practice point 4.3)

Fig 20 from KDIGO guidelines

Comments

Pharmacotherapy of T2D is extended as an addition to lifestyle interventions which alone may not suffice for glycemic control. A combination of metformin and SGLT2 inhibitors are suggested by the KDIGO workgroup as first-line treatment for most patients with an eGFR ≥ 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 rather than exclusive monotherapy with either metformin or SGLT2i. Indeed the KDIGO work group suggests addition of SGLT2i to patients on metformin even when glycemic targets have been achieved despite limited supporting data.

It is reasonable to consider this approach due to the different mechanisms of action and low risk of hypoglycemia with these classes of drugs. SGLT2is reduce kidney disease progression and cardiovascular mortality independent of eGFR despite only a modest beneficial effect on HbA1c (0.7% reduction) compared to metformin (1.5% reduction). Factors such as availability, cost, drug coverage and patient acceptance of potential risks vs benefit of SGLT2is will determine adaptation of this approach.

The authors suggest that neither metformin nor an SGLT2i should be initiated in patients with T2D and an eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Metformin should be discontinued below an eGFR of 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2. However patients who are initiated on an SGLT2i at an eGFR >30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and subsequently decline to an eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, the SGLT2i can be continued until initiation of kidney replacement therapy based on the approach of CREDENCE (Perkovic et al NEJM 2019). In the DAPA-CKD (Heerspink et al NEJM 2020) trial dapagliflozin was used in patients with eGFR as low as 25ml/min/1.73m2 paving the path to further explore the benefits of this class of drugs in advanced CKD.

Patients with eGFR ≥ 30 ml/min not achieving glycemic control with lifestyle and first-line pharmacotherapy and those with an eGFR < 30 ml/min need other classes of antihyperglycemic drugs. Among the second line pharmacotherapy GLP-1 receptor agonists are preferred over DPP-4 inhibitors and others because of their demonstrated cardiovascular benefits, particularly among patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), and possible kidney benefits. Cost concerns and the need for injecting GLP-1RA remain important barriers until oral GLP-1RAs become available.

Metformin

The KDIGO work group recommend treating patients with T2D, CKD, and an eGFR ≥30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 with metformin (1B)

Treat kidney transplant recipients with T2D and an eGFR ≥30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 with metformin according to recommendations for patients with T2D and CKD. (Practice point)

Monitor eGFR in patients treated with metformin. Increase the frequency of monitoring when the eGFR is <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (Practice point)

Adjust the dose of metformin when the eGFR is <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and for some patients when the eGFR is 45–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (Practice point)

Monitor patients for vitamin B12 deficiency when they are treated with metformin for more than 4 years. (Practice point)

Comments:

Due to low cost, wide availability and proven beneficial effects on weight, cardiovascular mortality metformin remains a first line anti-hyperglycemic agent for T2D in CKD. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) showed metformin monotherapy in obese patients was comparable to sulfonylureas or insulin in reducing fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c with lower risk of hypoglycemia and with CV benefits. The initiation and dosing of metformin should be guided by the eGFR, as discussed above.

Wait! isn’t there a high risk of metformin associated lactic acidosis (MALA) in CKD?

Here is an excellent perspective on MALA by Tom Oates, and a NephJC discussion of a subsequent study. The KDIGO and FDA seem to concur, thankfully. The association between metformin and lactic acidosis is inconsistent even in patients with eGFR of 30-60 ml/min/1.73m2. In 2016 FDA revised its recommendation to use metformin in CKD to include patients with eGFR >30 ml/min/1.73m2.

There is scant data to guide use of metformin after kidney transplantation. A small pilot RCT of metformin in impaired glucose tolerance after kidney transplantation (Transdiab, Alnasrallah et al, BMC Nephrol) concluded metformin is safe to use. In view of lack of data against its use after transplantation the KDIGO work group suggests use of metformin in the transplant population using the same approach as for CKD group.

Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i)

For the only 1A recommendation in the entire document:

KDIGO recommends treating patients with T2D, CKD, and an eGFR ≥30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 with an SGLT2i (1A).

An SGLT2i can be added to other antihyperglycemic medications for patients whose glycemic targets are not currently met or who are meeting glycemic targets but can safely attain a lower target. (Practice point)

For patients in whom additional glucose-lowering may increase risk for hypoglycemia (e.g., those treated with insulin or sulfonylureas and currently meeting glycemic targets), it may be necessary to stop or reduce the dose of an antihyperglycemic drug other than metformin to facilitate addition of an SGLT2i. (Practice point)

The choice of an SGLT2i should prioritize agents with documented kidney or cardiovascular benefits and take eGFR into account. (Practice point)

It is reasonable to withhold SGLT2i during times of prolonged fasting, surgery, or critical medical illness. (Practice point)

If a patient is at risk for hypovolemia, consider decreasing thiazide or loop diuretic dosages before commencement of SGLT2i treatment, advise patients about symptoms of volume depletion and low blood pressure, and follow up on volume status after drug initiation. (Practice point)

A reversible decrease in the eGFR with commencement of SGLT2i treatment may occur and is generally not an indication to discontinue therapy. (Practice point)

Once an SGLT2i is initiated, it is reasonable to continue an SGLT2i even if the eGFR falls below 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, unless it is not tolerated or kidney replacement therapy is initiated.(Practice point)

SGLT2i have not been adequately studied in kidney transplant recipients, who may benefit from SGLT2i treatment, but are immunosuppressed and potentially at increased risk for infections; therefore, the recommendation to use SGLT2i does not apply to kidney transplant recipients. (Practice point)

Comments:

SGLT2i lower blood glucose by inhibiting tubular reabsorption of glucose. They also have a diuretic effect and alter metabolism by promoting ketogenesis over carbohydrate utilization. SGLT2i confer a modest reduction in HbA1c (~0.7%), blood pressure (~4.5mmHg) and weight (~1.8kg). Despite these modest results, there is robust evidence supporting the renoprotective and cardioprotective effects of SGLT2i from multiple RCTs. That they did not extend the recommendation to kidney transplantation is interesting, considering that it is allowed for metformin. Perhaps we should accept this since the progression of kidney disease in kidney transplant has many other facets including immunological factors, such that even RAS blockade may not be favorable (Hiremath et al, AJKD 2017).

Check out the NephJC summaries of EMPA-REG, CANVAS, CREDENCE and DAPA-CKD as well for more.

The chapter ends with a section on GLP-1RAs.

In patients with T2D and CKD who have not achieved individualized glycemic targets despite use of metformin and SGLT2i treatment, or who are unable to use those medications, we recommend a long-acting GLP-1 RA (1B)

followed by a few practice points on how best to use them.

Fig 27 from KDIGO guidelines

Comments

Why are GLP-1RAs a 1B, and follow metformin and SGLT2i? They do demonstrate clear CV benefits, but their kidney benefits are mostly driven by an albuminuria reduction. They do have favorable cardiometabolic effects however (weight loss, amongst others). A few practice points follow as well for the interested person.

Chapter 5: Approaches to Management of patients with diabetes and CKD

We recommend that a structured self-management educational program be implemented for care of people with diabetes and CKD (1C)

Interestingly enough, there are trials in this area, though with mostly surrogate outcomes and high level of heterogeneity, hence downgraded to 1C. See below for some of that:

Figure 29 from KDIGO guidelines

This chapter ends with another exhortation to team based care

We suggest that policymakers and institutional decision-makers implement team-based, integrated care focused on risk evaluation and patient empowerment to provide comprehensive care in patients with diabetes and CKD (2B)

Discussion

Overall this is an excellent document, and reminds one of the KDIGO GN guidelines which provided useful clinical nuggets. This will be a document which will remain (mostly) useful for quite a while to come.

Good:

Elevation of SGLT2i as 1A and first line with metformin.

Lots of practical guidance for SGLT2i usage

Bad:

Evidence level overall remains low with only one 1A recommendation, and plenty of 1C, 1D and 2C recommendations as well as ‘practice points’.

Ugly:

Some interesting decisions remain

Metformin remains first line (is the evidence for this as strong as it is for SGLT2i? See Neuen et al 2020)

Avoid ACEi + ARB as a practice point not a recommendation

All the low evidence based nutrition recommendations that go against current trends are puzzling as well.