#NephJC Chat

Tuesday, April, 5th, 2022 at 9 pm Eastern Standard Time

Wednesday, April, 6th, 2022 at 9 pm Indian Standard Time and 3:30 pm GMT

BMJ 2022; 376; e064604

The effects of plasma exchange in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis

Michael Walsh, David Collister, Linan Zeng, Peter A Merkel, Charles D Pusey, Gordon Guyatt, Chen Au Peh, Wladimir Szpirt, Toshiko Ito-Hara, David R W Jayne, Plasma exchange and glucocorticoid dosing for patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis BMJ Rapid Recommendations Group

PMID: 35217545

Introduction

Plasma exchange and ANCA-associated vasculitis

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) associated vasculitis (AAV) is a multi-system disease and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Despite treatment with immunosuppressive agents, patients remain at high risk of death, end stage kidney disease (ESKD), and serious infection, particularly in the first year of treatment (Little et al, Ann Rheum Dis 2010). Hence, there is an ongoing quest to develop more efficacious treatment regimens for this condition.

Plasma exchange (PLEX) has been used as adjuvant therapy in the management of AAV for many years. However, the role of PLEX in AAV has had a tumultuous path. Some may ask if we even need to talk about PLEX in AAV again, particularly after the recently published PEXIVAS (Walsh et al, NEJM 2020) trial divided the nephrology community into two camps (to PLEX or not to PLEX).

This week the #NephJC chat will focus on the most recently published systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of PLEX in patients with AAV (Walsh et al, BMJ 2022). Will the potentially surprising conclusions from this systematic review overturn some of the recent pessimism the renal community has felt about the use of PLEX in this dreadful medical condition? Or will this be the final time that NephJC discusses the use of PLEX in AAV?

What prior evidence supports the use of PLEX in ANCA-associated vasculitis?

The majority of the evidence for the use of PLEX as adjuvant therapy in AAV, along with immunosuppressive therapies, came from the basis of biological rationale and smaller clinical trials conducted in the 1980s-1990s. Landmark trials in AAV can be found here.

In 1991, Pusey et al. demonstrated, in a small cohort of 48 patients, that the addition of PLEX to immunosuppressive therapies resulted in higher rates of renal function recovery in patients with AAV who were initially dialysis-dependent (p=0.041), and this was maintained even at long term follow-up (Pusey et al, Kidney Int 1991).

Subsequently, the MEPEX (Jayne et al, JASN 2007) trial demonstrated that dialysis independence at 3 months was higher in the patient cohort that received PLEX compared to those who received intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone alone (they recruited 137 patients across 9 European countries with AAV and serum creatinine (SCr) >500 umol/l [5.7 mg/dl]. While the short term results were encouraging, a long term follow-up of the same cohort showed that the risk of death or ESKD was in fact similar at 3.95 years post-treatment (hazard ratio for the primary composite endpoint of death or ESKD was 0.81, 95% CI: 0.53-1.23) (Walsh et al, Kidney Int 2013).

Long term data from the trial conducted by Szpirt et al. showed improved renal survival at 1 and 5 years in patients with AAV who received PLEX compared to those who did not (p<0.01 in patients with initial SCr >250 umol/l [2.8 mg/dl]), with no difference in morbidity or mortality between the two groups (Szpirt et al, NDT 2011) - but the n was just 32.

Fast-forward to 2020, the PEXIVAS trial railroaded through the New England Journal of Medicine, questioning everything we previously knew about PLEX in AAV. The trial randomized 704 patients with AAV and eGFR <50 mL/min (including those needing dialysis) or pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage (PAH), to PLEX vs no PLEX along with standard care. Results did not show a benefit of PLEX on the primary composite outcome of death and ESKD (hazard ratio 0.86, 95% CI: 0.65-1.13) after a median follow-up of 2.9 years (Walsh et al, NEJM 2020).

Nearly a third of these patients (n=205) met the MEPEX inclusion criteria, yet there was no effect of PLEX on the primary outcome in subgroup analysis. It is important to note that there were some fundamental differences between the MEPEX and PEXIVAS trials (broader inclusion parameters and the lack of mandatory biopsy at baseline in the latter). Nevertheless, the investigators did a tremendous job of recruiting such a large number of patients across the globe, which as far as trials in nephrology go, is a game-changer in itself! PEXIVAS was discussed in detail previously on NephJC.

The results of PEXIVAS certainly led to some turmoil in the nephrology community, most of whom had been pro-PLEX prior to the trial. PLEX is associated with several adverse effects including serious infections, bleeding and clotting abnormalities, and allergic reactions to replacement fluid. PLEX requires central venous access (itself associated with the risk of bleeding and infection) and requires specialized staff and equipment. So the risks and benefits need to be carefully considered.

After the results of PEXIVAS were published, many physicians would still advocate for the use of PLEX in patients with AAV who are concomitantly positive for anti-GBM disease (KDIGO guidelines, Kidney Int 2021). Some would also still advocate for the use of PLEX in patients with significant PAH, despite no benefit demonstrated in PEXIVAS, while others might be more concerned about the risk of bleeding and infection risk even in this group. Nephrologists seem divided on the use of PLEX in those patients with severe active AAV kidney disease.

Two systematic reviews by Walsh et al, (AJKD 2011) and Walters et al (Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020) – the former conducted prior to the PEXIVAS, and the latter including some PEXIVAS data from the conference proceedings – reported that the use of PLEX was associated with a lower risk for progression to ESKD, but had no effect on patient mortality. In the face of PEXIVAS showing no benefits, do we have enough rationale to curtail the use of PLEX altogether? Or would a further meta-analysis give us a more nuanced answer?

The Study

Eligibility criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Study design: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Study population: Patients with AAV or rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis of which >75% of cases were considered pauci-immune or idiopathic

Intervention: PLEX by any method and in any dose as initial treatment in addition to immunosuppression and glucocorticoids

Outcomes: Trials that report at least one of mortality, ESKD, serious infection (needing hospitalization or IV antibiotics), disease relapse, adverse events (SAE) or health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

Time: Outcomes reported at 12 months after randomization or later

Studies were eligible irrespective of whether they were published or unpublished and irrespective of languages

Exclusion criteria:

Studies were excluded if they included primarily children (>75% under the age of 16 years).

Risk of bias assessment:

The Cochrane tool was used to assess the risk of bias which included: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, staff and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other risks.

Certainty of evidence assessment:

This was assessed using the GRADE approach (i.e., the certainty of a minimal important effect being present). This was chosen by the BMJ Rapid Recommendations group including absolute risk differences of 2% for mortality, 3% for ESKD, and 5% for serious infections. Commonly used thresholds were used for HRQoL instruments. Ratings of certainty included consideration of risk bias, inconsistency, precision, and indirectness.

Statistical analysis:

For each outcome, the random-effects model was used to estimate the average relative risk (RR) across trials and the corresponding 95%CI. The proportion of total variability in effect estimates due to between-study heterogeneity (I2 statistic) and estimated the between-study variance (T2).

Subgroup effects were explored by comparing subgroups with a SCr of >500 umol/l [>5.7 mg/dl] or needing dialysis and subgroups with a SCr of <500umol/l and not needing dialysis. Thai was based on prior studies that concluded important effects of PLEX were limited to those with worse kidney function. Subgroup analysis was also explored based on patients with or without PAH at baseline. Trial sequential analysis was used to examine the conclusiveness of the estimates. Absolute risk reduction was calculated across a range of baseline risks for outcomes with conclusive results. The risk stratification was based on baseline serum creatinine as follows:

Low risk (SCr ≤200 μmol/l [≤2.3 mg/dl]),

Low-moderate risk (SCr >200-300 μmol/l [>2.3-3.4 mg/dl]),

Moderate-high risk (SCr >300-500 μmol/l [>3.4-5.7 mg/dl]), and

High risk (SCr >500 μmol/l [5.7 mg/dl] or requiring dialysis).

Results

Nine randomized controlled trials were included in the meta-analysis which included data from 1060 patients with a median follow-up of three years, as depicted in Figure 1.

The characteristics of the nine studies included in the meta-analysis are summarized in Table 1. These include the small trials done in the 1980-90s, the MEPEX trial and its long-term follow-up study, long-term results from the trial conducted by Szpirt, et al, and the recent PEXIVAS trial. Apart from the MEPEX and PEXIVAS trials, most studies recruited small numbers. The length of follow-up varied from 12 months to 127 months.

Table 1: Characteristics of trials of plasma exchange for treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis and participants included for meta-analysis (from Walsh et al, BMJ 2022)

Five trials were at low risk of bias for random sequence generation and four were at low risk of bias for allocation concealment. Eight trials were considered at low risk for bias from incomplete data, and all nine were considered at low risk of bias from selective outcome reporting. While none of the trials were blinded, given the objective nature of the outcomes (death, ESKD, and serious infections defined as need for hospitalization or IV antibiotics) that are unlikely to be affected by observation bias, the risk of bias was considered low for all studies.

Outcomes

All-cause mortality

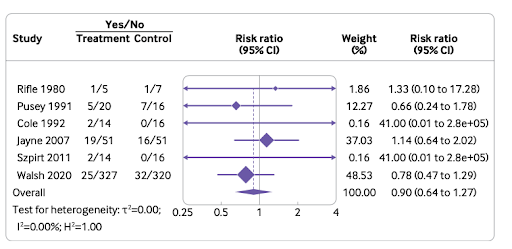

PLEX in all likelihood did not show any effect on all-cause mortality. The effect of plasma exchange on all-cause mortality was documented at:

12-month follow-up in 967 patients in six trials: relative risk [RR] 0.90, 95%CI: 0.64 to 1.27, moderate certainty

Longer-term follow-up in 1028 patients in eight trials: RR 0.93, 95%CI: 0.73 to 1.19, moderate certainty.

This effect on all-cause mortality is independent of baseline kidney function and the presence or absence of pulmonary hemorrhage.

Figure 2. Effect of PLEX on all-cause mortality within 12-months’ follow-up in patients with AAV (from Walsh et al, BMJ 2022)

End-stage kidney disease (ESKD)

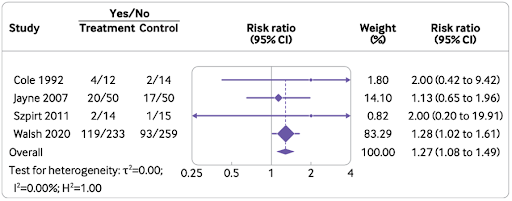

PLEX probably reduced the risk of ESKD at 12 months but may not necessarily affect long-term risk (Figure 3). The effects were documented at:

12-months follow-up in 999 patients in seven trials: RR 0.62; 95% CI: 0.39 to 0.98

Longer-term follow-up in 996 patients in seven trials: RR 0.79, 95% CI: 0.58 to 1.08, low certainty

The estimated absolute risk reduction (ARR) in ESKD for PLEX was most (16%) in those with the highest risk (SCr >500 μmol/L or needing dialysis, high certainty of important effects) compared to those at lowest risk (SCr <200 μmol/L [<2.3 mg/dL], high certainty of no important effects; ARR 0.08%).

Figure 3. Effect of PLEX on end stage kidney disease within 12-months’ follow-up in patients with AAV (from Walsh et al, BMJ 2022)

Serious infections

The risk of serious infections associated with PLEX:

An increased risk of serious infection at 12 months (908 patients in four trials- RR 1.27; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.49, moderate certainty)

Possibly an increased risk at longer follow up (957 patients in six trials- RR 1.13; 95% CI: 1.03 to 1.24, low certainty), (Figure 4).

The estimated absolute risk increase for serious infection with PLEX was 2.7% for those at lowest risk (SCr < 200 µmol/L, moderate certainty) compared to 13.5% for those at high risk (SCr >500 µmol/L or needing dialysis, moderate certainty).

Figure 4. Effect of PLEX on risk of serious infections at 12 month’s follow up in patients with AAV (from Walsh et al, BMJ 2022)

Relapse

PLEX had no effects on relapse of vasculitis with 202 patients in three trials developing a relapse at the long term (RR 0.92, 95% CI: 0.32 to 2.67, low certainty).

Other serious adverse events (SAE)

PLEX had little to no effect on other SAEs at 12 months (one trial with 137 patients, RR: 1.05, 95%CI 0.74 to 1.48, moderate certainty) and at longer-term follow up (three trials with 750 patients, RR: 1.00, 95%CI 0.89 to 1.11, moderate certainty).

Health related Quality of life

Unfortunately, only PEXIVAS examined this important, patient-focussed question. In PEXIVAS no differences were seen in any measures of HRQoL at 12 months (one trial with 704 patients, moderate to high certainty).

Discussion

Does this systematic review and meta-analysis herald the end of an era for PLEX or has this ‘perPLEXed’ you further? Could the use of PLEX be reasonably continued in certain high-risk patients? Or does the risk of serious infectious complications render its use unjustifiable in patients with AAV?

The results of the present meta-analysis are promising in terms of decreased risk of ESKD at 12 months (moderate certainty) in patients with AAV who receive PLEX therapy, counter-balanced however, by a high rate of serious infections. Contrary to the early decreased risk of ESKD, there was no continued risk reduction of ESKD at longer-term follow-up, and the risk of serious infection also probably diminished over time. As would be expected, the absolute risk reduction across the range of baseline risks showed minimal risk reduction in patients at the lowest risk and substantial risk reduction in those at the highest risk. There is no effect of PLEX on all-cause mortality in patients with or without pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage. These results are in agreement with a previous systematic review and meta-analysis by the same group (Walsh et al, AJKD 2011).

Though the results of the meta-analysis are not particularly in favor of PLEX in AAV, do we have any guidance as to when PLEX might actually be indicated in AAV? In a recent editorial, lead author Michael Walsh suggested that the beneficial effect of PLEX in AAV depends on the extent of renal involvement (Walsh, JASN 2022). PLEX should probably be considered in patients who have severe renal disease, where the benefits of PLEX surpass the risks of treatment.

So do we have any risk scores in vasculitis by which one predicts the risk of ESKD at presentation? There are a few risk scores described in AAV namely Berden classification which takes into account the percentage of crescents, Mayo clinic/Renal pathology society chronicity score which is based on both glomerular and tubulointerstitial involvement, and the Brix score or ANCA Renal risk score which incorporates both histopathology and GFR at diagnosis (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Classification/scoring of kidney involvement in AAV (from Kronbichler, et al KI 2018)

A recent retrospective study by Nezam et al. attempted to determine which set of patients with AAV would benefit from PLEX. They included a cohort of 425 patients, of which 188 patients were treated with PLEX. The primary outcome was mortality or renal replacement therapy at 12 months. This study concluded that there is an absolute risk reduction of 24.6% for the primary outcome at the end of 1 year in the PLEX group. Microscopic polyangiitis, MPO-ANCA, higher serum creatinine, crescentic and sclerotic classes, and higher Brix score were observed in the PLEX-recommended group. Though there was no effect of PLEX on the primary outcome in the whole study population, the authors suggested a certain subset of patients might benefit from PLEX based upon the risk scores determined by baseline kidney function and histopathology.(Nezem et al, JASN 2022)

So what do all these results mean from a practical perspective? Does the promise of a short-term reduction in dialysis requirement suffice to administer an expensive adjuvant therapy that is associated with side effects including serious infections? Serious infections were defined as those needing IV antibiotics or hospitalization. This meta-analysis suggests that PLEX is likely to provide some benefit in patients who are at ‘high risk of developing ESKD, but it is also the same group that are likely to be at ‘high risk of developing serious infections. Concerningly, despite recent strides made in the management of AAV, the pervasive lack of mortality benefit has been consistent across previous systematic reviews and reflects the significant burden of this disease.

From a clinician’s point of view, the short-term benefits of kidney function may be a useful metric, however, we lack adequate data from this review on what this means for patient preferences and quality of life. There was only one trial in this review (PEXIVAS) that measured health-related QoL, and unfortunately, there was no benefit seen. Whether this is due to residual chronic kidney disease, need for aggressive immunosuppressive therapies and associated side effects, recovery from a serious infection, or other factors, is difficult to pinpoint. This systematic review may help clinicians counsel patients with AAV across a range of baseline risks and inform shared decision-making with patients and their caregivers.

BMJ recommendations

Based on this review, the BMJ guideline panel recommends against the use of PLEX in patients with low or low-moderate risk of developing ESKD (i.e. less severe disease with SCr <300umol/l, weak recommendation). They make a weak recommendation in favor of PLEX in patients with moderate-high or high risk of progressing to ESKD (i.e. more severe disease with SCr >300umo/l or needing dialysis). They do not recommend using PLEX in patients with PAH without renal disease (weak recommendation).

Strengths of the study

This review captured a larger number of patients with a long duration of follow-up and reported on important outcomes using the GRADE approach to determine the certainty of evidence.

Limitations of the study

There was a moderate degree of heterogeneity across the various studies included in this meta-analysis. Obviously, given PEXIVAS supplies the majority of the data, any criticism of PEXIVAS will translate into concern about the conclusions of this meta-analysis. Factors such as the inclusion of an unknown number of relapsing patients and lack of kidney biopsy have been raised by some as short-comings of this trial. Unfortunately, we still lack granular data regarding what disease process was the cause of death for patients in PEXIVAS.

Take Home Message

The current evidence does not demonstrate a role for PLEX in addition to standard care with glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive therapies in preventing death in AAV. It is possible that PLEX delays the need for dialysis by some months, especially in higher-risk patients, but this is at the cost of potentially developing serious infectious and other complications. Additionally, PLEX is expensive, invasive, and resource-intensive. Gauging the cost-effectiveness of this treatment modality, the potential short-term effect on risk reduction for ESKD, and the complex trade-off for the risk of infections should form the basis of shared decision-making with patients and their caregivers.

Summary prepared by

Anoushka Krishnan, Nephrologist,

Perth, Australia

Priyadarshini John, Nephrologist

Hyderabad, India

NSMC Interns, Class of 2022

Reviewed by

Jamie Willows, Jade Teakell, Brian Rifkin