In a previous post on NephJC stats, we briefly touched on the misinterpretations surrounding the p-value, problems with multiple comparisons and understanding the difference between ‘statistical’ and ‘clinical’ significance.

In this post, let’s look at the implications surrounding ‘underpowered’ studies, and understand why it is crucial to differentiate these from ‘negative’ studies.

A 2016 NEJM review titled ‘Primary outcome fails - what’s next?’ highlighted this issue. Studies where the primary outcome has a p-value over 0.05 are traditionally referred to as “negative”. Is the case closed?

“The simple answer is NO!”

It is important to take a step back and consider other aspects of a so called negative trial.

Table 1 from Pocock and Stone, NEJM 2016

An underpowered study is one in which insufficient individuals were enrolled (or data points obtained) to draw a meaningful conclusion. These are potentially bad. They expose study participants to risk without providing meaningful knowledge. The inclusion of too few patients in a study increases the risk that a significant treatment benefit will not be seen, even when such an effect exists (type-2 error).

A negative study is one where enough individuals were enrolled to show that there is no difference between the treatment and control. Negative studies advance science.

Effect Size Matters

The effect size facilitates the comparison of treatment effects between clinical trials on a common scale. An effect size is the magnitude of the difference between treatment groups. It is important to determine what is the minimum clinically relevant difference. For example - A pill that reduces blood pressure from 150/80 to 149/80 might not be worth the cost, risk or cognitive burden.

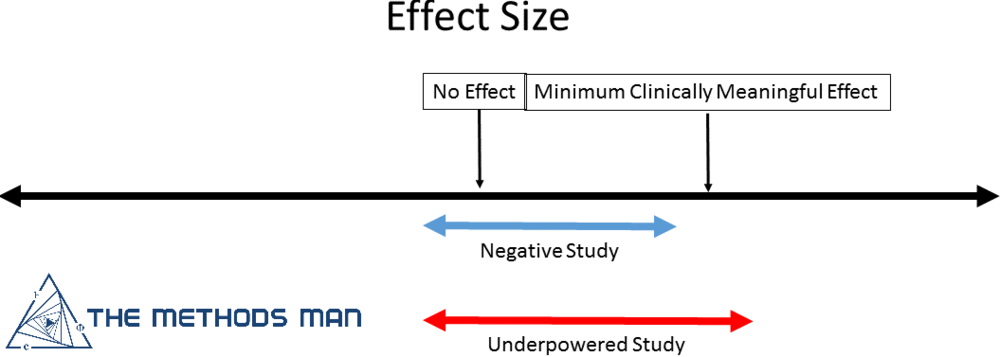

It is possible to have a large effect with a non-significant p-value (> 0.05) if the sample size is small leading to the conclusion of “no effect” which is the main problem with underpowered studies. This can result in discarding the possibility of a meaningful and clinically significant effect.

So how do you decide if the trial is simply underpowered or truly negative?

- If the confidence interval (CI) of the effect size INCLUDES the minimally important difference, your study is underpowered

- If the confidence interval of the effect size EXCLUDES the minimally important difference, your study is negative.

From the MethodsmanMD blog, who does have a positive effect despite the logo placement

Most commonly, the 95% confidence level is used which means that if the trial is repeated multiple times with different sample sizes, 95% of times, the effect size will lie between these CI.

Thus, it is important to pre-specify the minimal clinically relevant difference between the effect of two treatments. The smaller the difference, the larger the required sample size. A power level of 80% is generally acceptable in most clinical research studies which implies that the study will detect a true difference 80% times and a true difference will be missed 20% of the time. This is a compromise because raising the power to 90% or 95% would entail a substantial increase in the sample size, increasing the cost and time to run the study.

For more on effect size and related calculations, read Effect Sizes.

Watch this wonderful video on the interpretation of negative trials by Perry.

For more on sample size and power, check out Sample Size: A Practical Introduction.